The chat app is a table-stakes feature for any dating app. A responsive and reliable messaging experience encourages users to stay on the platform for communications. This is desirable from a trust and safety standpoint, as abusive messages produced on the platform can be effectively moderated and proper actions can be promptly taken.

In this article, we will explore the design of an offline-first chat app on the OkCupid website, in particular, how we achieved responsiveness by implementing optimistic UI design patterns and reliability by incorporating a messages cache to support offline-mode.

Table of Contents

Why do we need the chat app to be offline-first?

Quick response time from the server is not always achievable, especially when the user is on a slow network on a mobile device. Offline-mode support is common for mobile apps because mobile apps often have to deal with spotty internet connection.

When do we need offline-mode support for a web app? There are two main reasons:

1. If the web app is used in a mobile web browser on a phone where reliable network connections are not guaranteed.

It’s common for a web app that runs in a desktop browser and the web app that runs in a mobile browser to share code (sometimes they are the same web app!). On mobile web, being offline is a real possibility.

2. If the web app is managing user-generated data that is expensive for the user to create.

In a chat app, it can be frustrating user experience if you spend a long time drafting a new message to be sent but the draft is not persisted when the message fails to send, forcing you to have to type it all up again.

The desktop version of popular chat apps like iMessage, Whatsapp, and Facebook Messenger all support offline-mode so users expect offline-mode support for any chat app regardless of the device.

What does offline-first mean exactly?

An app is considered to be offline-first if it can be used even when the user is offline.

An app that is designed to be offline-first supports unpredictable network latency by default.

We can think of being offline to mean having infinite network response time.

When the app is completely offline, the POST request for new content never resolves. If the app is designed to be offline-first, we would expect the app to still show the new content (responsiveness) and to still allow us to create newer content without losing the previously created new content (persistence).

Responsiveness is achieved by applying optimistic UI techniques. To make user interactions seem instant in a CRUD app, we can mock the expected server response before the server response is received and display the mocked response (the optimistic result). Optimistic results are things that exist client-side but not server-side.

How and where we are storing the optimistic results becomes important when we want to provide persistence.

Things can get very hairy when we need to persist an arbitrary number of optimistic results and these optimistic results need to be displayed alongside things that exist server-side.

We will discuss that in more detail in the solution approach section. But first, let’s look at the design decisions behind the offline-first OkCupid chat app.

Architectural Design Considerations

The previous section answers the question of why we need to have offline-mode for the chat app. This section answers the question of How we should implement an offline-first chat app for OkCupid.

In general, to design a correct and future-proof solution, we must first consider the requirements and constraints to establish the boundaries for our problem-solving. Second, we must decompose the problem into sub-problems and search through the solution space for the best way to solve these sub-problems.

Requirements Gathering

Understanding the scope of the problem requires insight into the business context of the problem we are solving and how the solution will need to scale for future use cases.

There are must-have and nice-to-have requirements for a modern chat app. The best way to enumerate the functional requirements for a feature is to use user stories. As a user, I want to be able to send and receive messages so that I can communicate with other users. More specifically,

- When I first open the chat app, I want to see the most recent messages exchanged between me and the other user.

- I want to be able to draft a new message and send it to the other user.

- I want to see the new message I sent to appear in the chat app immediately after I send it.

- I want to see the new message the other user sent appear in the chat app immediately after the other user sends it.

- When the other user sees my message, I want to immediately see the message marked as read.

- When I scroll up in the chat app, I want to see older messages appear.

- I want to be able to send a new message even when I am offline.

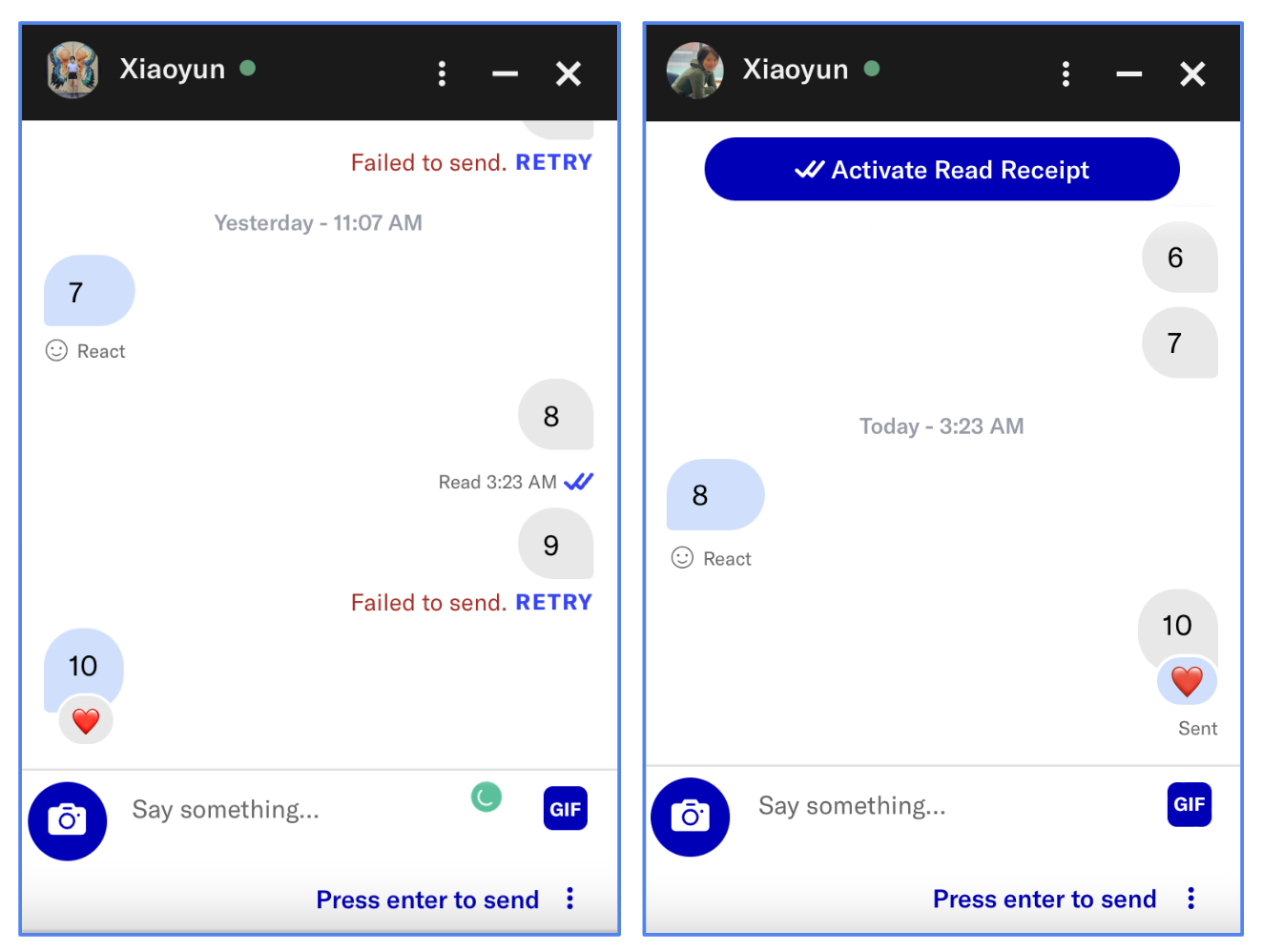

- If I try to send a new message when I am offline, I want to see the message appear in the chat history with a status indicating that this message has not actually been sent.

- When I am online again, I want a simple way to resend the messages that I tried to send when I was offline. It would be nice if the resend is automatic.

Functional requirements include the features we need to support now but the solution design should also consider future features. The better we can anticipate future requirements, the better we can make good initial design decisions to create a robust and scalable solution that can easily adapt to new use cases.

A non-scalable solution cannot evolve to support new requirements without costly refactoring or special-case handling, which introduces maintainability concerns. But when too much emphasis is put on future-proofing, we end up with an over-engineered solution that is also hard to scale and maintain.

Scalability and maintainability are examples of non-functional and business requirements that we also want to optimize for. For the chat app, we don’t want to use a general offline-mode implementation that can be used for both collaborative data as well as non-collaborative data because this implementation can be very demanding on memory usage and computationally intensive. Using a memory- and power-intensive implementations not only causes unnecessary technical complexity in the implementation (bad for maintenance and velocity to launch the feature) but also a degraded offline-first experience from lagginess and crashes on cheap phones without a lot of processing power and memory.

Collaborative data is not a future use case we will ever need to support for the chat app. As previously mentioned, only one person can create and edit a message and this is true for any chat app.

What are some valid and likely future features we would want to ship for the OkCupid chat app? We can look to other chat apps to see what features they have that make sense for a dating app.

- Threaded reply - Very Likely. Almost all modern chat apps support threaded reply. Bumble, another dating app, already implements threaded replies in their chat app.

- Group chat - Likely. OkCupid is one of the best dating apps for daters seeking non-traditional relationships and already provides the ability for partnered daters to link their profiles together. It would be on-brand for OkCupid to provide a way for daters to chat with multiple people at once.

- Un-send a message - Unlikely because it is undesirable from a trust and safety standpoint, allowing bad actors to un-send a message will make it difficult to moderate a reported conversation. This feature is also not present in Bumble’s chat app.

- Edit a sent message - Unlikely. Same reason as un-send a message.

Identify Constraints

Unconstrained problem-solving can be liberating but also overwhelming when there are too many choices to consider.

When we are searching for an optimal solution for a problem in a solution space, applying constraints can help us better scope our problem and refine our search to discover a simple and practical solution.

There are two flavors of constraints in engineering problem-solving: feasibility and practicality.

Feasibility

Feasibility concerns technical constraints that are imposed by the current technology we are using.

For example, a feasibility concern for the chat app may be memory availability on the device that the chat app runs on.

A conversation can have an arbitrarily large number of messages. If we load all the messages into memory without pagination when the app first mounts, we will quickly run out of memory and the app will crash.

Practicality

Practicality deals with business constraints like engineering resources, budget, timeline, and tolerance for risk.

Choosing to pursue a more technically complex and robust solution at a higher engineering cost is not always appropriate for a business that needs to be agile to test hypotheses and iterate quickly.

A social media platform like OkCupid operates in a very competitive landscape so there’s an urgency to launch quickly and iterate on experimental features in response to new market insights. A flexible architectural design that is easier and faster to implement but has more technical debt is often the right choice for OkCupid.

Another practicality constraint is the tolerance for risk which depends on the business case for the feature. For example, if the KPI is measured in the number of new user onboarding and conversion of these users to paid users, the business cost of shipping a broken onboarding flow or broken table-stakes feature like matching and chatting can be very high. In this case, it is better to trade off velocity for higher code quality.

Other Things We Want to Optimize for

Maintainability is a goal for any software engineering project. We want to make sure that the solution we implement is consistent with the existing patterns in the codebase and is easy to maintain.

Code complexity is a source of maintainability concern.

A more technically complex solution may be more robust but it also introduces more risk of bugs and crashes. A more technically complex solution may also be more expensive to maintain and scale.

There’s a non-recurring upfront cost to develop a solution and recurring cost to maintain and evolve the solution.

The recurring cost can often be higher than the upfront cost because the upfront cost is amortized over the lifetime of the product.

Engineering effort is required not only to implement the solution but also to maintain and evolve the solution over time. The more complex the solution, the more effort is required to maintain and evolve the solution.

One way to offset the upfront cost is to use a third-party solution. But this comes with the risk of vendor lock-in and the cost of integration.

To lower recurring cost, many codebases use industry standards and have style guides to discourage deviations from existing patterns because inconsistencies in codebases add maintenance cost.

Another way to lower maintenance costs is to avoid duplication of code. Duplication is generally considered tech debt it makes the codebase hard to evolve (you have to make the same changes in multiple places), which could introduce inconsistency in the codebase and bugs.

However, duplication is not always bad! Sometimes it makes things simpler. As complexity can also be a source of maintainability concern. Sometimes it could be a good tradeoff to introduce a little bit of duplication for a lot of simplicity.

Solution Approach

To make the chat app offline-first, we need to find a way to manage a collection of ordered data (messages between two users) which can be added to the collection by the server or by the user. Server-added messages come from an API request or a WebSocket event. Client-added messages come from the user sending a message.

We can think of the offline-first chat app as a collaborative editing tool - two users are collaborating on the same conversation thread. The conversation thread is a collection of messages ordered by the time they were created. A collaborating session in the context of a chat app is when all the participants of the chat are online and actively contributing to the conversation.

This insight provides a clear direction for our problem-solving because it helps us identify and tackle the sub-problems in collaborative editing systems using established design patterns.

Sub-problem 1: Source of Truth

Offline-mode support is unachievable if we don’t keep a local copy of the data that the client can operate on while offline.

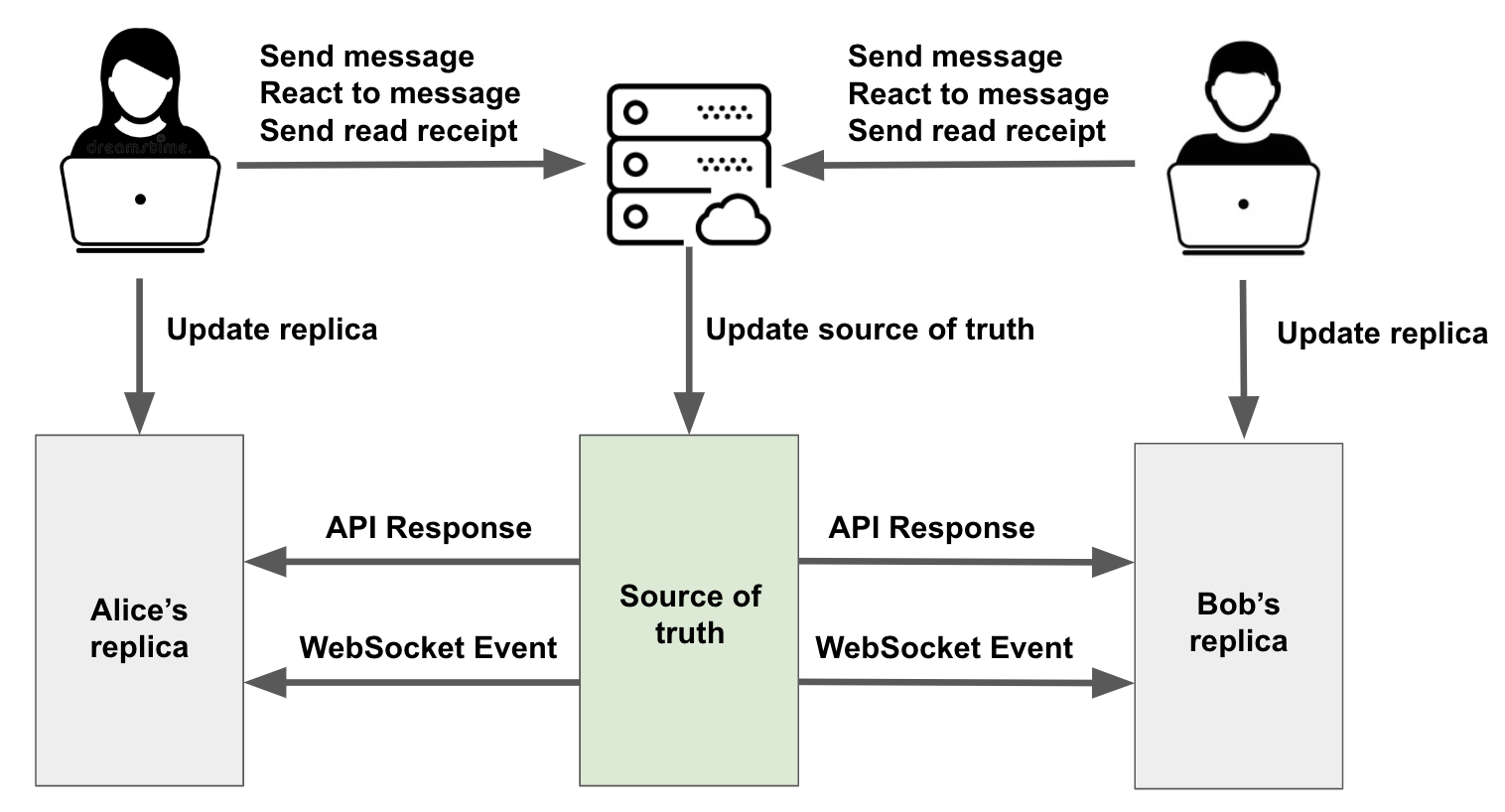

Replication is a fundamental idea in collaborative editing systems. The basic idea is that we let the server maintain the source of truth for the conversation thread and we make a copy (replica) of that conversation thread on each client.

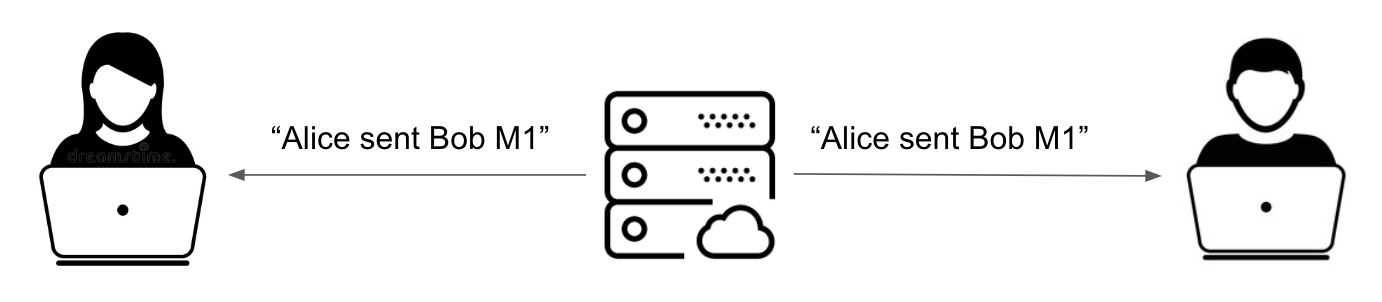

Each client operates on their replica based on events from the server or the user but only the server is allowed to make updates to the source of truth.

The clients collaborate on making changes to the source of truth by sending update requests to the server and syncing server states with their respective replica states.

Does the source of truth need to exist on the server? Not necessarily. In decentralized systems where there is no single authority to determine the final state that every client needs to be on. All replicas can reach eventual consistency using techniques that are widely deployed in distributed systems like massive-multiplayer-online-games and peer-to-peer applications. It would be interesting to see how distributed computing techniques can be applied to web applications so that our data is not owned by a centralized authority like OkCupid (the premise of the Web 3 movement).

But in our Web 2 world, we have a server that is the gatekeeper for communications between two users as we see in this example.

When Alice and Bob first open their chat app, their replicas are populated by the source of truth from the server via an API request. A WebSocket connection is also established between their clients and the OkCupid server to stream any updates to the source of truth.

Alice and Bob can make changes (mutations) to the source of truth in these ways:

- Send (and re-send) a message

- React to a message

- Send a read receipt

Next, we will look at how we keep the replicas in sync with the source of truth when mutations are applied.

Sub-problem 2: Consistency Maintenance

In our chat app system, we have two replicas of the conversation thread on Alice and Bob’s devices. We would like to keep the replicas in sync with each other. In a chat app, you can’t really have a conversation when your replica is showing a different chat history than your conversation partner’s replica.

The replicas can become out of sync when Alice and Bob are proposing changes to the conversation thread (e.g., adding a new message to the thread or reacting to a message).

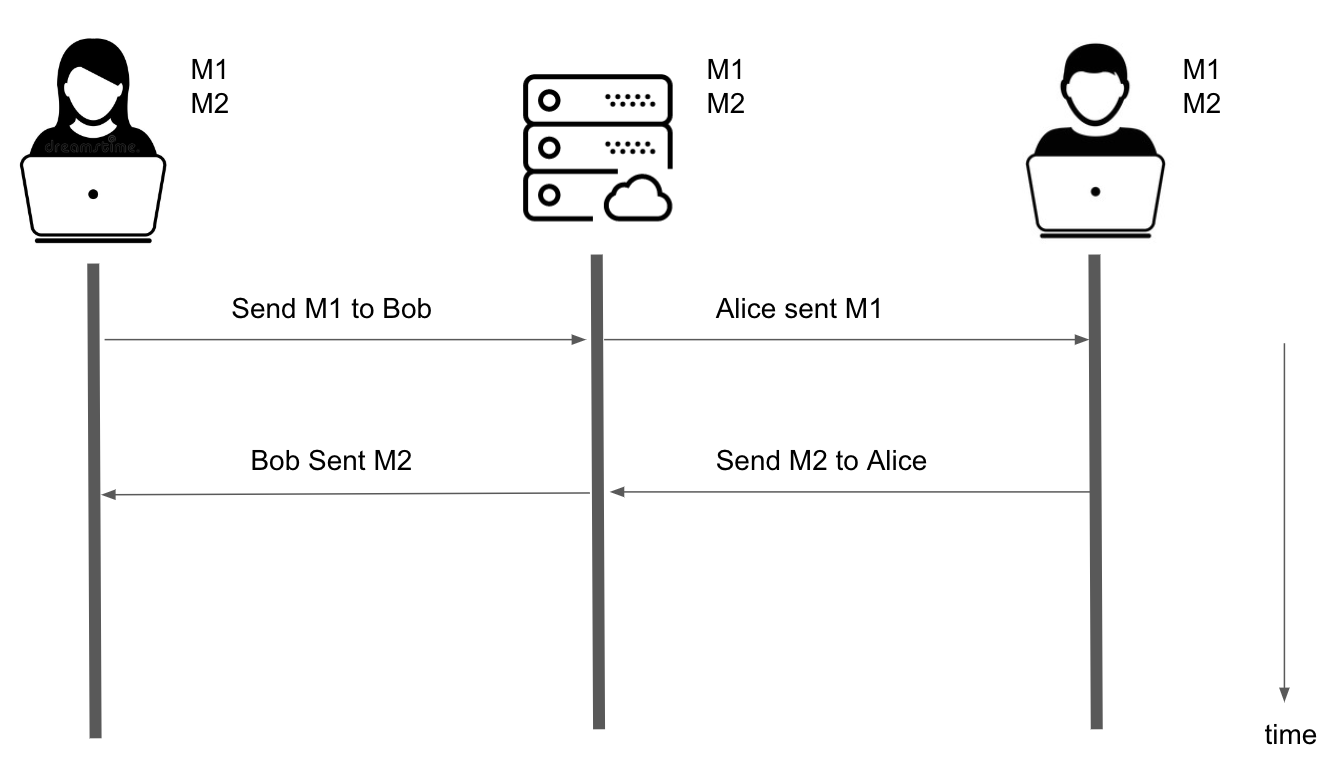

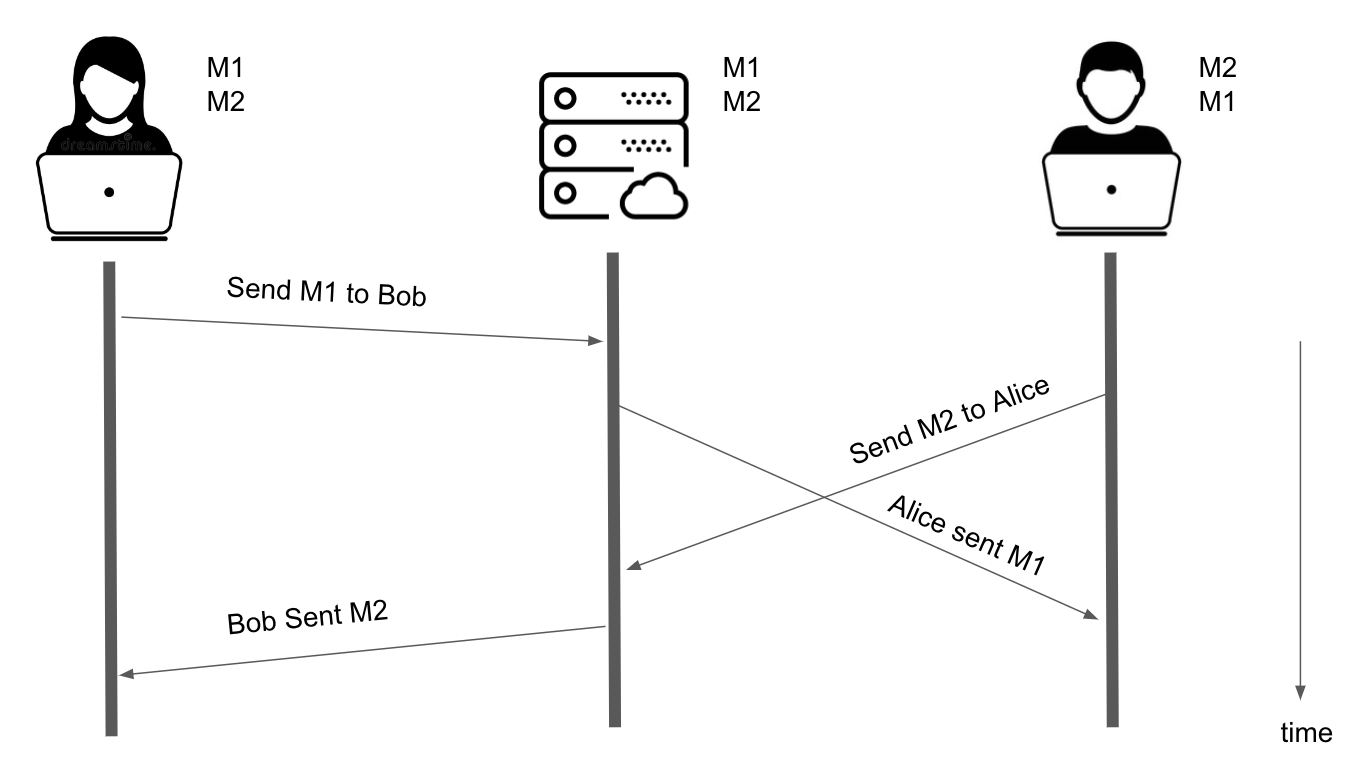

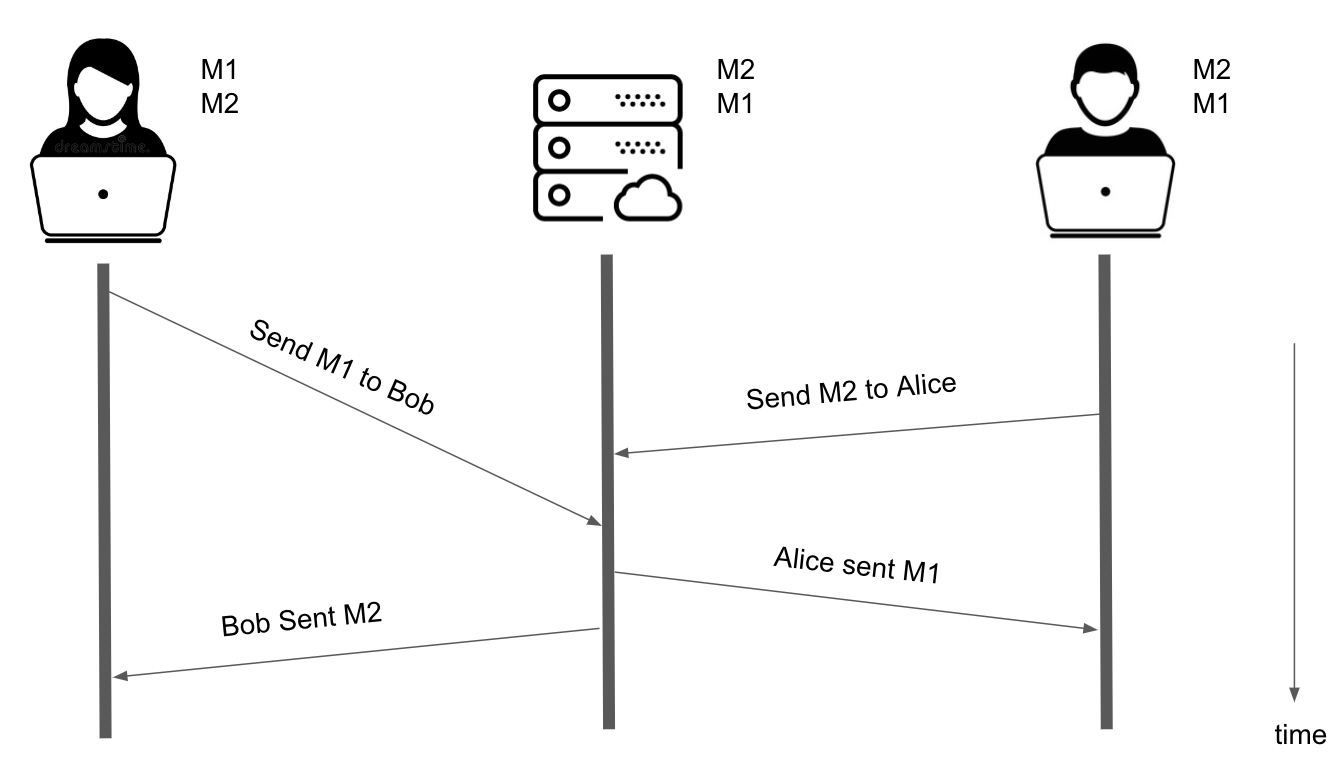

Suppose Alice wants to send Bob a message M1, Alice makes a request to the server to update the source of truth after applying the change optimistically to her replica. Meanwhile, Bob is drafting a message M2 to Alice and sends it shortly after Alice sends M1.

In a perfect zero-latency world, Alice and Bob will get each other’s messages instantaneously and their replicas will always be in sync.

In the real world, server and network latencies both contribute to the order in which mutation requests are processed and broadcasted, which affects what Alice and Bob eventually see in their steady-state replicas after all the messages are done being sent and received.

For instance, when the server receives the request from Alice, it needs to do some work which takes time. Maybe it runs some expensive checks on the incoming message for inappropriate content before it adds the message to the database (which also takes time) and broadcasts that mutation to Bob. You can implement timeouts in the server-client contract to provide some guarantee that the mutation will be successfully processed in a given window of time but there is still some variability in the server latency.

This variability is a potential source of non-determinism and divergence (inconsistency) in the replicas.

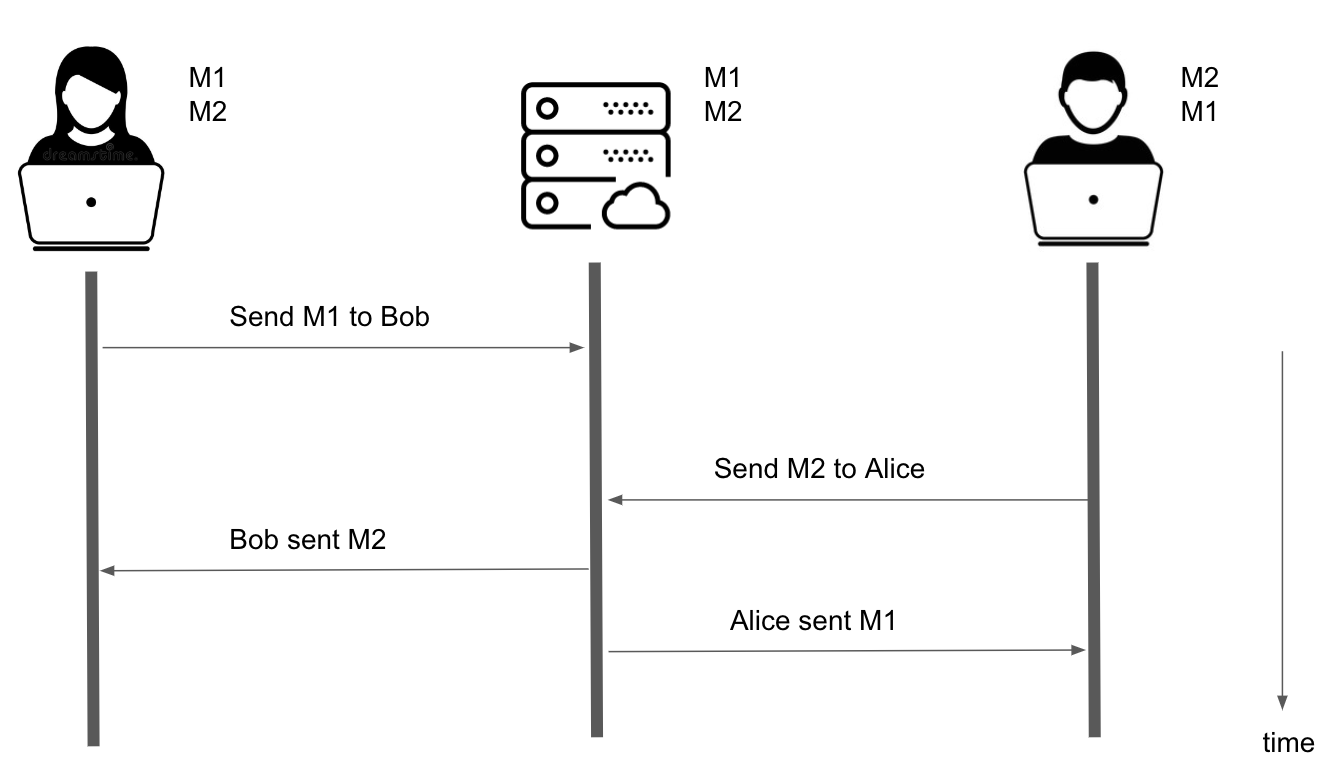

We also have to worry about network latency. As illustrated by the sloped lines in the figure below, it takes some time for requests to travel from Alice’s and Bob’s devices to the server and from the mutation event to travel from the server to Alice and Bob through the WebSocket connection.

Look what happens when Bob is on a really slow network.

But there can be another configuration for the latencies stack-up where the server will process Bob’s request before Alice’s request.

In all these non-ideal real-world cases, all the latencies in the system cause the replicas to diverge. In the modern era of multi-tiered network abstractions (NAT WiFi, VPN, cloud computing, Docker, etc.), trying to make predictions about how the different latencies will stack up is an exercise in futility. The final states of all the copies will be non-deterministic unless we implement some policy for reconciling the differences between these copies.

In our example, we see a divergence in the order of M1 and M2 at the different replica sites and the server. Because we designate the server as the keeper of truth, the server version of the messages is a key component in our reconciliation strategy. However, we need to first address the non-determinism in the order of the messages that exist server-side.

The invariant for our collection is that messages are always ordered by the time they were created. This needs to be true for all copies of the data (replicas and sources of truth).

But there can be different interpretations of “time of creation”. Is it the time when Alice sends M1? Or is it the time when the server adds M1 to the database? What does “time of creation” for M1 mean to Bob?

If we were to make the “time of creation” be the time when the server adds the message, we would introduce more entropy into the system as we see in the last example where the server version of the order of the messages is influenced by network latency.

We can remove non-determinism in the server version of the messages order by forcing the server to recognize the “time of creation” for a message to be the time at which the client sends the mutation request to the server. This way, the “time of creation” as recognized by the server is consistent with the “time of creation” for the client (Recall when the client sends a message, it also adds the message optimistically to the replica).

Now we have established that the timestamp is the basis for the real order of the messages and is consistent between the sender and the server, what does “time of creation” mean for the receiver?

TODO: in the messages cache implementation, need to update the timestamp of message that will be re-sent to reflect the retry send time rather than the time of the last send attempt.

Sub-problem 3: Conflict Resolution (Or Avoidance?)

Each client’s replica is modified by local action and remote updates. Conflict arises when the locally updated data disagrees with the data upstream.

Let’s revisit the example when Alice and Bob are messaging each other.

When Alice sends M1 to Bob, that mutation is propagated to Bob via a WebSocket event. You can think of the WebSocket event as a broadcast the server makes to all the clients that are subscribed to changes to the conversation thread. The server doesn’t care who is on the receiving end of the broadcast. It announces to every participant in the conversation that something has changed and each participant needs to decide what to do with that information.

When Bob receives the WebSocket event, he needs to add M1 to his replica because he doesn’t have that message already. There are some nuances with how he should add the message to his replica which we’ll get to that in the next section.

But let’s first focus on Alice. When Alice receives this event, she can do one of two things:

- Ignore the event or

- Process the event by making some changes to her replica without causing a conflict.

Because Alice was the one who sent M1, she already added that message optimistically to her replica. Recall, optimistic UI works by simulating the result before the server responds. If the M1 from the server is identical to the optimistically added M1, she can choose to ignore the event.

However, in OkCupid’s chat app, the real id is decided when a message is added to the database. The client implementation uses a pseudo-random generator to create a unique id for the optimistic message before adding it to the replica (let’s call this tempId).

function generateTemporaryMessageId() {

return `${Math.round(Math.random() * 10000)}`;

}

The tempId looks something like 4306 while the real id looks something like 18325309058943693999.

When Alice adds a message optimistically to her replica, she can simulate almost everything in the final result except the id.

The id is an important part of the message identity as it assigns uniqueness to each message in the replica collection. The id can be used to look up a particular message in the replica which supports various business logic. The id is also an important part of the view creation logic as it is used as the key in the React render function that maps an array of messages to JSX.

Resolving conflict in the two different id versions should be avoided. We are venturing into dangerous territories when the clients are in the business of reasoning about the provenance of data in its local copy. This could introduce a leaky abstraction problem wherein the client needs to know the implementation details of the server (e.g., how an id is picked), which can cause the system to be fragile and error-prone.

There are two ways to avoid performing conflict resolution on the id. Choosing which approach to pursue depends on the constraints and non-functional requirements imposed on the project. In particular, this is a tradeoff between technical complexity on the back-end vs front-end.

Conflict Avoidance (server-side)

A server-generated id for message was a constraint for the offline-first chat app project. The chat app was originally built to not be usable while offline. Users could not create new messages to be queued for sending while they are offline.

If we were building an offline-first chat app from scratch, we could have totally avoided the two different versions of id by making the real id client-generated.

Here’s the idea:

- For the new message, the client generates a UUID then send that to the server.

- The server implements format check, duplicate check, and date check on the UUID. If any of these checks fail, reject the message send request.

This approach does not alleviate the clients from tracking what’s real and what’s optimistic in their replicas but it significantly simplifies the replica implementation as it can be implemented as a growth-only set. A separate data structure can be used to track the outgoing messages that are not server-approved (e.g., a Set containing the UUIDs of messages in the outbox).

Conflict Avoidance (client-side)

This is the approach taken for the OkCupid offline-first chat app implementation. The general idea is to implement a policy for “merging” the server-generated id into optimistically added message in the replica.

For sent message in the replica, we must maintain both its the server-generated id and the tempId.

-

Because the replica data is used for business logic, simply ignoring the server-generated

idand only usingtempIdwould cause problems when we need to make another mutation to the message (e.g., marking the message as read which requires updating a property on the message in the replica). -

Because the replica data also drives the view, replacing the

tempIdwith the server-generatedidwill also cause problems because the messageidis used as thekeyby React to render the message. If we simply replace thetempIdwith the server-generatedid, we are going to experience a very noticeable flicker where React will unmount the optimistically added message and mount the server-added message.

The merge policy in more detail in the Solution Design section.

Sub-problem 4: Eventual Consistency

Replicas can become out-of-sync with each other during the collaborative editing session but we need to guarantee that the states kept in the replica will eventually converge.

To better visualize the problem of divergence, let’s look at the following scenario:

- At t =

T0, Alice goes offline - At t =

T1, Alice tried to send a messagesM1(send fails) - At t =

T2, Bob sendsM2 - At t =

T3, Alice goes online again. WebSocket is re-established - At t =

T4, Alice sendsM4 - At t =

T5, Bob sendM5 - At t =

T6, Alice re-sendsM1

What Alice sees at t = T6:

M4

M5

M1

What Bob sees at t = T6:

M2

M4

M5

M1

What Bob sees is consistent with what the server sees at T6 but there’s a divergence (inconsistency) between Alice’s chat history and Bob’s chat history. This is because when Alice comes back online at T3, Alice’s client does not download a fresh copy of the chat history from the server. It only syncs the messages sent after a new WebSocket connection is established.

We avoid the need to solve the conflict resolution problem by keeping the client version after the network connection is established again and not forcing it to be consistent with the server version. As there’s no polling, the only server-driven update to the client replica is from WebSocket events.

The OkCupid chat app lets you go offline for an arbitrary amount of time and continue sending new messages. However, when you are online again, it doesn’t automatically download all the messages sent to you when you were offline and re-apply your offline edits on top of the latest state.

Choosing an appropriate final state when concurrent updates have occurred is called reconciliation and can be quite tricky to implement.

For instance, there’s a downside to simply syncing the replicas with the server state when the system reaches steady-state: It can violate the invariant for our collection wherein messages are always ordered by the time they were created. This has some usability implications as it can create a jarring user experience to see the messages in the chat history suddenly change order.

optimistic replication allows replicas to diverge. Replicas will reach eventual consistency the next time Alice and Bob sync their replicas with the server state, which only happens when they refresh their chat apps (reload the page).

This seems like kind of a cheat but convergence upon system quiescence is a common strategy to achieve eventual consistency. This relieves us from having to implement an explicit reconciliation policy for the replicas which could be unnecessarily complex for our problem space.

Avoiding reconciliation simplifies the implementation of our CDRT. The insufficient real-time support is a limitation of our approach but is good enough for OkCupid’s use case because in a dating app, we don’t expect people to be chatting simultaneously for a long period of time like they would in Slack.

But if you are building a real-time chat app where simultaneous communication is a common use case, you will need to implement offline detection/polling the latest server data and merge the server data into the replica.

Sub-problem 5: Intention Preservation

All the strategies for implementing collaborative editing tools are guided by a set of principles depending on which consistency model is used.

For the implementation of OkCupid’s chat app, the CCI consistency model was considered. It includes these three properties:

Causality preservation

ensures the execution order of causally dependent operations be the same as their natural cause-effect order during the process of collaboration.

Convergence

ensures the replicated copies of the shared document be identical at all sites at quiescence (i.e., the final result at the end of a collaborative editing session is consistent across all replicas).

Intention preservation

ensures that the effect of executing an operation at remote sites achieves the same effect as executing this operation at the local site at the time of its generation.

Causality preservation and convergence are essential properties of any consistency model to ensure the correctness of the system during and after a collaboration session.

The causally dependent operations include optimistically adding the message with client-generated tempId to the replica, then when the server approves the mutation, replace the optimistic message with the real message with the server-assigned id, including a tombstone for what it was before when it was optimistically added (we will talk about this later in the implementation of the chat app CRDT).

While a serialization protocol can be used to achieve causality preservation, it cannot be used to achieve intention preservation. The reason is that the serialization protocol does not have access to the user’s intention.

Intention preservation is an obvious goal in a chat app because the point of the chat app is to facilitate a conversation between two people where messages are created in response to other messages. The order of messages as they appear at each replica site is important for the conversation to make sense.

Why we need intention preservation is best argued by considering a situation if we don’t impose intention preservation:

Alice asks Bob a question and sees that the question is optimistically added to her replica of the chat history. In the meantime, Bob is typing up a response to another question Alice asked a day before. If Alice is on a really slow network, Bob will not see her new question come into his chat history until some time after he sends his reply to her old question. Bob’s intent is for Alice (the remote site) to see the new message as a response to her old question but because of network latency, Bob’s message will be misunderstood by Alice as a response to her new question. Bob’s intention is not preserved.

How do we prevent this misunderstanding? When Alice gets the event announcing that a message has been added to the conversation by Bob, rather than simply adding the message to the end of her chat history replica, she can perform some comparisons based on the message timestamps to insert Bob’s message in the right place in her chat history. This is possible because the real order of the messages is determined by the timestamp, which is created by the sender client at the time of creation (when the message is sent).

TODO: add this timestamp comparison logic to the messages cache implementation.

Solution Design

This section focuses on the implementation of the replica used in the OkCupid chat app.

There are many optimistic replication and multiplayer functionalities implementations out there in collaborative editing tools such as Google Docs, Notion, Figma, and Peritext.

Studying these reference designs helped us get some general ideas about how to design the architecture for our system but the specific architecture choice depends on the the specific usage patterns for our chat app.

Answering these questions is a good starting point for the technology down-selection:

- What is the nature of the data that is being collaborated on?

- Does it need to be real-time (Synchronous)?

- What kind of mutations are supported?

We will answer these questions and investigate a different aspect of the architecture in the following sections.

Replica Data Structure

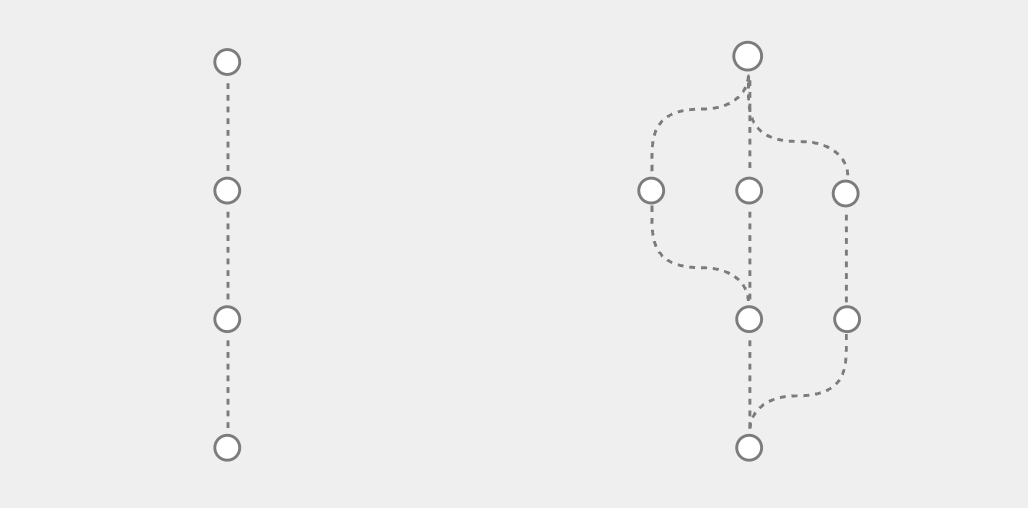

There are two types of collaboration models.

- The Google Docs model (pictured left) supports a real-time synchronous collaboration style where every update to the document form a single linear timeline.

- Asynchronous collaboration (pictured right) requires a Git-like model where users can create a private copy (branch) of the document and merge their branch into the main branch when they are ready to do so.

The most suitable architecture for our chat app is

. Answering these questions provided us good starting point to narrow our technology selection for the chat app:

Operational Transformation (implemented by Google Docs) and Conflict-free Replicated Data Types (CRDT) are the two most common classes for conflict resolution strategies.

In our offline-first chat app, we need to support real-time synchronous collaboration of a shared chat timeline. But the mutations are only adding (send a message) updating (reacting to a message and updating the read time of a message for read receipt).

Most suitable

The server and all the clients are managing their own copy of a growth-only set. The server propagates changes to the shared state to by transmitting the update operation. The server propagates changes to the shared state to by transmitting the update operation.

The chat app belongs to the first variant of collaboration style.

Operational transform implemented in Google Docs is overkill for our chat app use case. For a two-player chat app, we don’t need to worry about the case where two people are editing the same message property (e.g., body, reaction, read time) at the same time because that’s not a valid use case. OkCupid’s chat app does not even allow users to update the body of a sent message.

If the chat app supports more than two players, then we need to implement conflict resolution for reactions and read times on a message. While that’s a future use case we don’t have to address now, it’s worthwhile to make our solution design general enough to support an arbitrary number of multi-players to it can be easily scaled for that future use case (which we identified earlier as a likely future use case).

A CRDT is an excellent choice for our problem because the data we are managing is a list of items.

With CRDT, we get conflict resolution for free because a CRDT is a data structure that automatically resolves any inconsistencies that might occur during updates. The replicas are kept in CRDT and can be updated independently and concurrently without coordination with other replicas or the server. A final property of CRDT is eventual consistency, which will look at a little later.

CRDT is a relatively new concept formalized in 2011 and popularized by collaboration tools like

There are various CRDTs to choose from. Notion and Figma both created their own CRDTs which target the specific problems they are solving. We will do the same for OkCupid’s chat app.

Map and Doubly Linked List

Merge Policy

Server-Approved Sent

- Delete Optimistic Message and replace with server-approved message

- Tombstone

- Resend a message - look at reference design

Local Storage

Apollo Client Cache vs Component State vs. Ref or Memo

Update Event Handling

- Send Optimistically

- Send Approved

- Resend

- Receive New Message

- Receive Reaction

- Receive Read Receipt

View Rendering

tempId vs real id