How I Get 100 Hours Worth of Work Done in a 40-hour Work Week

I spend 3 hours at the gym every day, go on mountaineering and snowboarding trips every three months, work as a founding engineer at a Series A startup, and still have time for side projects like this blog post.

Someone recently asked me what’s my secret for getting all this done. How do I have time to do all these things?

In this blog post, I’ll share my secrets on how to be hyper-productive using some theories from business books I read and insights from science (e.g. three laws of thermodynamics), with examples from my experience climbing, training at the gym, and working as a software engineer.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Conservation of Energy

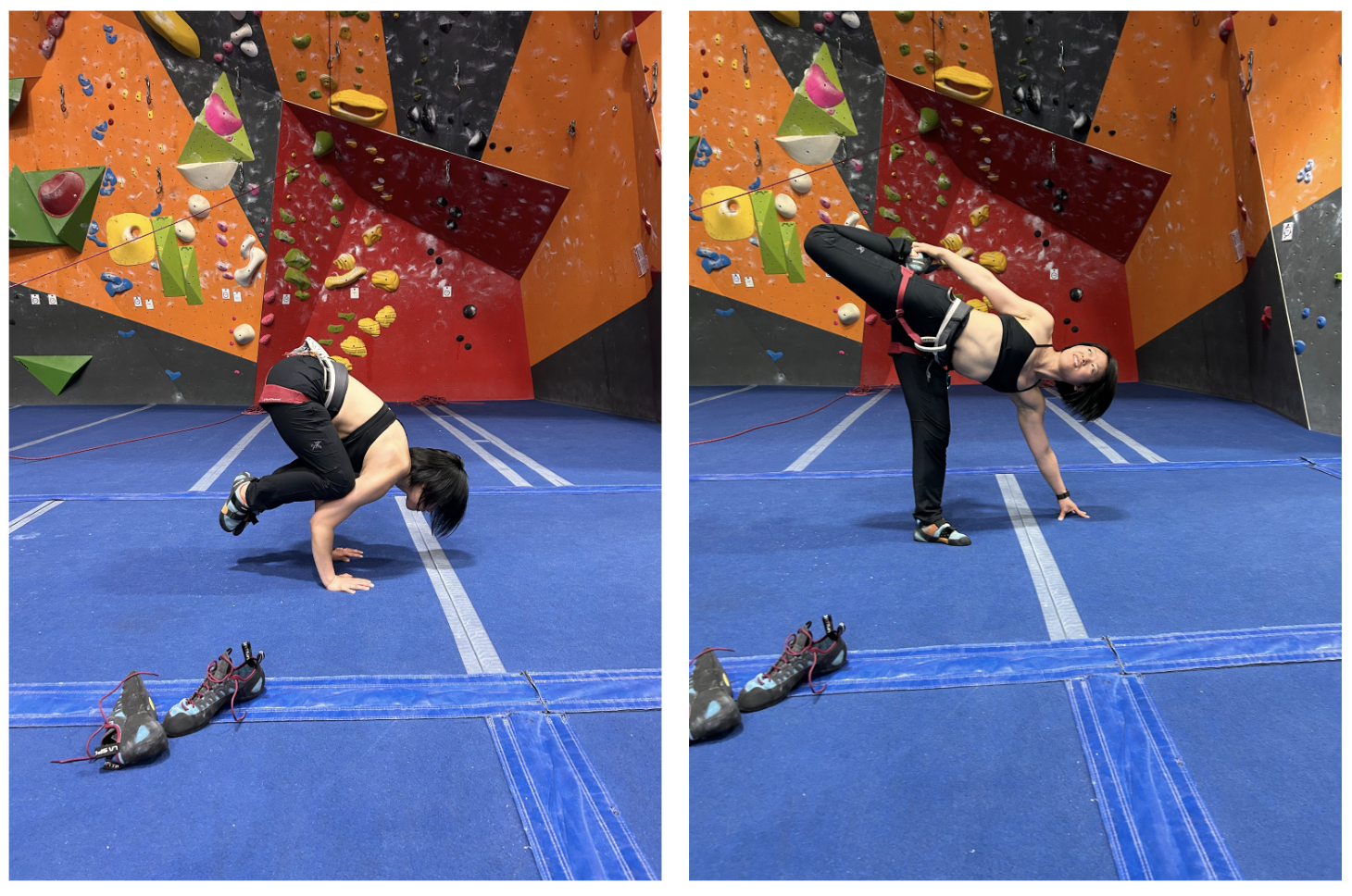

Ai Mori, a 5-foot-tall climber from Japan became the climbing world champion by using a climbing style that emphasizes conservation of energy.

One of her greatest strengths is that she can figure out creative ways to make a series of small static movements to send big walls. Small static moves are more energy efficient than big movements. Another one of her strengths is that she always keeps her body in a triangle shape, which provides a strong stable base and allows her legs to climb up rather than relying more on her upper body strengths.

Conservation energy is a fundamental theory of excellence in everything in life, whether it’s sports like climbing, yoga, running, scaling a business, or living a fulfilling life.

Look around for the easier and non-obvious solutions

During an approach to a crag in Wales, my guide Rich told me something that really struck a chord with me:

It’s tempting to go for the obvious big rock to step on but there are lots of smaller rocks that are closer that you can use to save you some energy.

To reach the summit, you need to conserve as much energy as possible so you can move fast and execute those hard moves when you really need to.

There are lots of paths to reach your goal but the best path is not the most obvious.

Whether you are climbing a mountain, solving a hard problem, or building a business, there are lots of little steps you have to take to get there. Before taking the next step, it’s important to scan the area for the most energy-efficient way of reaching the next milestone.

The trick is to actively identify things you do that are energy inefficient and see if there’s a lower-effort way to help you accomplish the same thing. I prefer the energy-efficient approach even if it takes me longer and cumulatively more effort to achieve the same objective than the more direct and obvious path.

This may sound counter-intuitive. Isn’t the goal of productivity to be as efficient as possible with our time and effort?

The short answer is we are not machines and we can burn out. The most time-efficient way of accomplishing something may require a long sprint with no breaks. We can lose the ability to execute when we are only sleeping 4 hours a day and working 100-hour weeks. We can also lose the desire to pursue that goal when we are not regularly seeing incremental progress.

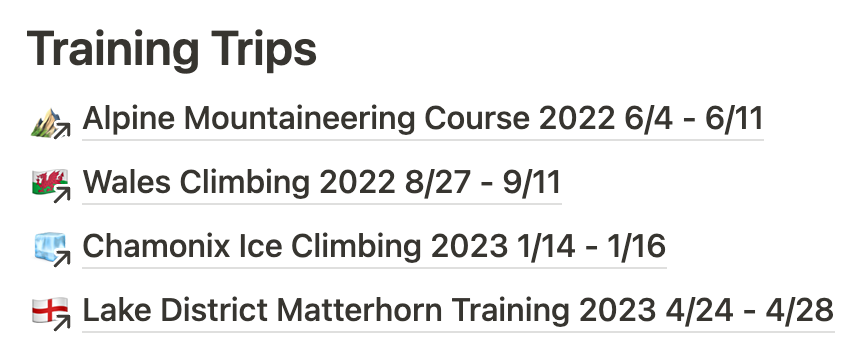

Let’s say you are starting at A and trying to go to B. The arrows represent the activities that can take you from where you are currently to where you want to be. The length of the arrow represents the effort of the activity.

There’s an obvious and direct way to get from A to B (take the blue path) but you can take the red path, which is broken down into smaller activities with milestones m1, m2, and m3.

These milestones provide “save points” for you to take a break from the project and re-evaluate whether you are still on the right track.

Although all the arrows of the red path will add up to be longer than the blue arrow, the red path breaks down the overarching task of getting from A to B into smaller, manageable chunks of easier work.

An approach that emphasizes saving energy is the winning strategy for getting anything done because it ensures a higher chance of completion by reducing the chance of burnout.

Another benefit of the energy-saving approach is solution reusability because it generally requires breaking down the problem into smaller sub-problems that can be solved more easily and composed later on to solve the bigger problem.

I will get into why that’s important in the next section.

How not to waste time

The definition of “a waste of time” is the allocation of time to a useless activity.

The “usefulness” of an activity is a function of personal values, individual preferences, and what you are trying to accomplish. Some people may consider watching reality TV as a useless activity but other people consider it useful in helping them relax.

I don’t like to think about “usefulness” as an intrinsic property of an activity. It’s meaningless outside the context of an overarching goal. An activity is useless if it doesn’t get you any closer to where you want to be.

No one ever deliberately plans to do something that is an obvious waste of their time but people often commit to doing something that can become a waste of time.

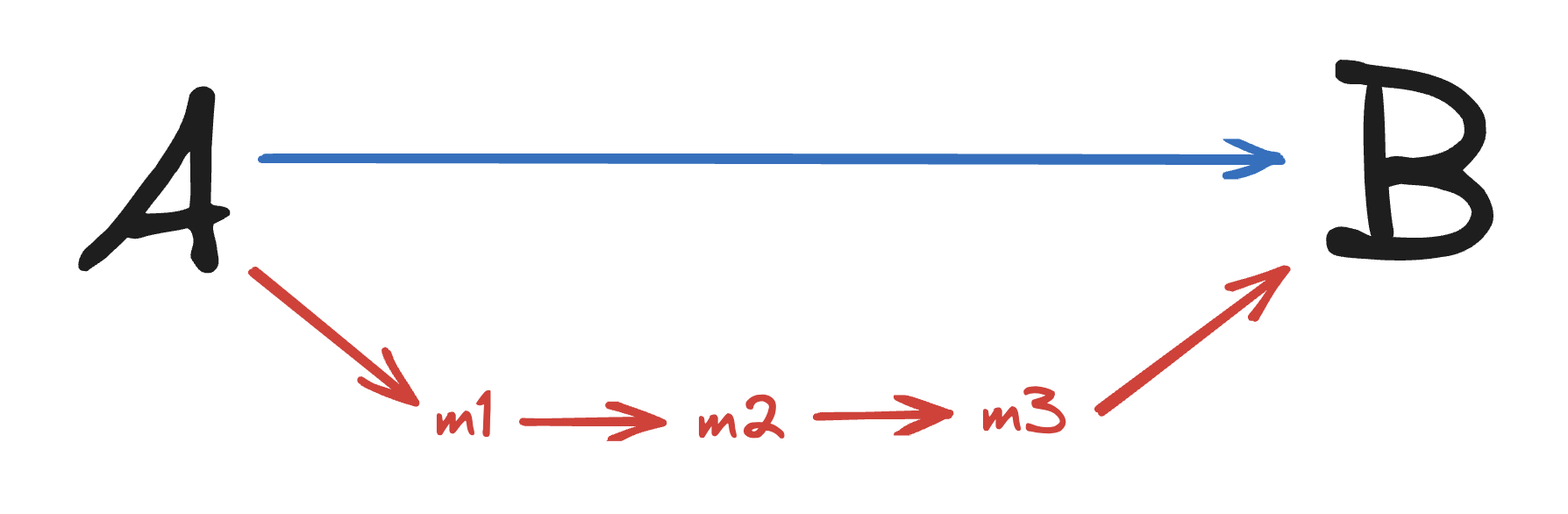

Let’s expand on the earlier example where you can take the blue path or the red path to get from A to B.

Suppose we chose the blue path. As we are halfway executing, we realize that B is not where we want to go. We actually want to go to C or maybe D. All the work we did on the blue path to B cannot be re-used to get us to C. It was a waste of time to get on the blue path because none of the distances we covered helped us get any closer to where we actually wanted to go.

An example of the “blue path” in real life is some bespoke solution you’ve built to solve a specific version of a problem. The bespoke solution is difficult to evolve when you realize that you actually want to solve a variation of the problem. If you had taken the “red path”, you would be solving the problem in a more modular or abstract way that if the goalpost moves, the work you’ve done can easily be tweaked to satisfy the changing requirements.

Another reason that makes us abandon the blue path is if halfway through executing, we realized that we underestimated the effort to take the direct path from A to B.

Instead of being shorter than the combination of red paths, it’s way longer. The original assumption that the blue path was shorter than the red path (the reason we chose blue over red) was wrong.

In How Will You Measure Your Life, Clayton M. Christensen, Harvard business school professor and author of the well-regarded The Innovator’s Dilemma, talks about the danger of single-mindedly focusing on executing a deliberate strategy.

Expecting to have a clear vision of where your life will take you is just wasting time. Even worse, it may actually close your mind to unexpected opportunities.

Everything we do in life has the potential to become a waste of time. The less trivial something is to accomplish, the more likely the approach we take can become a waste of time.

If we can find a way to break down a big non-trivial task into many small trivial tasks, then we can minimize the risk of wasting time in accomplishing the overarching task.

As Christensen points out, we can’t guarantee the outcome unless we implement something to test whether our deliberate strategy is valid. Plans change all the time when we discover something along the way that invalidated our assumptions upon which the deliberate strategy is based. Often, the most interesting and rewarding things we do in life are non-trivial and require us to commit to taking actions that can lead nowhere.

The takeaway here is not to become clairvoyant and be better at predicting whether our deliberate strategy will be successful. Rather, we should learn to be strategic in how to solve hard problems in a way that avoids wasting huge amounts of time.

A strategy that works for me is to pursue a discovery-driven approach that optimizes for testability, evolvability, and reusability.

- Testability: How quickly and easily can I check that I’m on the right track?

- Flexibility: How easy is it to pivot to a different direction if my initial assumptions were incorrect?

- Reusability: In the worst case when I have to pivot and abandon my original approach, how much of the work I’ve done previously can be leveraged so I don’t have to start from scratch?

In video games, when you choose the wrong approach and your character dies, you wasted a bunch of time but at least you can easily reload from the last save point and start again. That’s the best-case scenario for when you choose wrong.

But in real life, there’s usually no magical save-point device. Switching to a different path requires extra work from having to backtrack and clean up the mess you made. Sometimes the switching cost can be prohibitively high, forcing you to continue on the wrong path which takes you farther from where you actually want to be.

I call this anti-progress.

The work you do that leads you to be stuck on the wrong path is called negative work.

Don’t do negative work

Many of us were taught to measure productivity by throughput which is a function of the number of hours we put in and how many boxes we check off on our to-do list. This model works for manual labor like farming, construction, cleaning the house, working out at the gym, etc which have very tangible and predictable results.

However much of the interesting work we get paid a lot of money to do involves problem-solving. These problems are non-trivial and require creativity and experimentation.

Sometimes doing no work is better than doing some work.

This demands a different way of thinking about productivity.

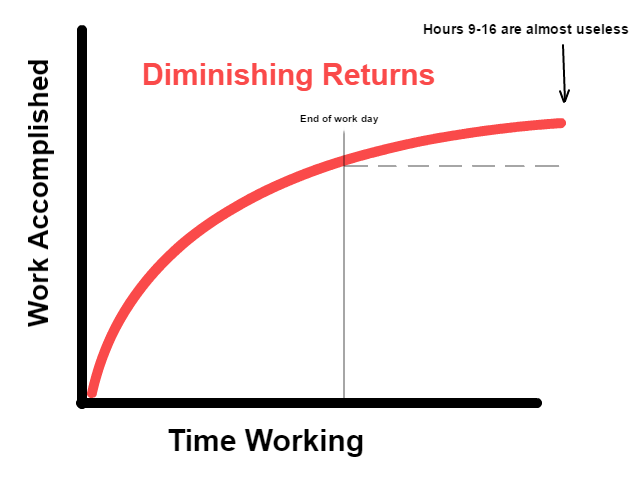

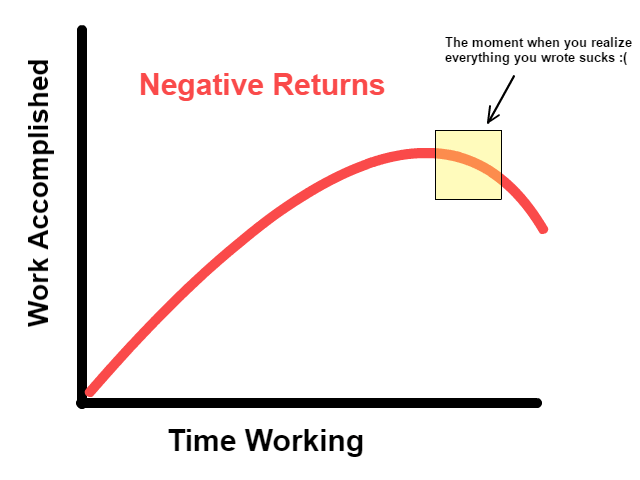

We’ve all experienced a time in which after working on something for a long time, we stopped making any more noticeable progress despite putting in exponentially more effort. This is called a point of diminishing returns.

The productivity curve can also turn negative when our sleep-deprived, tunnel-visioned brains start to make bad decisions.

Mark Manson puts it best in his post How to Be More Productive (While Working Less):

We all hit a point at which the more work we produce, the worse it is, which just creates even more work to fix your previous shitty work.

This happens all the time at work when a smart but inexperienced developer would spend too much time designing and implementing an over-engineered solution that becomes a huge maintenance burden for the rest of the team for years to come.

Other times, negative work is introduced when the developer doesn’t spend enough time to understand the problem and built something which hinges on an incorrect assumption, resulting in bugs and tech debt in the codebase.

In general, if the work you do will add negative overall value, don’t do it. This needs to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Negative work is often a result of trying to do too much too quickly.

At the gym, I often see New-Year-Resolutioners come in and work out really hard for the first 2 months of the year, then they stopped coming to the gym due to an injury from lifting too heavy or burning out from suddenly ramping up on their workouts by a lot when their body was not ready for it. If they had slowly and steadily ramped up their workout over the course of 6 months, they could have achieved the summer body they wanted by July.

An analog of this in business is when a startup tries to scale too quickly, they hire a lot of engineers to add a lot of features to their product. Then they realized that these features are actually really expensive to maintain so they have to hire more engineers to build internal tools to support those features. Then an unexpected event outside of anyone’s control leads to an economic downturn, making it really hard to raise money. The startup runs out of money and either goes out of business or if they are lucky, finds a bigger company to acquire them at a huge discount.

Chapter 2: How to spend your time

We all have things in our lives that are competing for our limited attention and resources. We have to make choices every day on how to best allocate our time. The so-called “sacrifice” we have to make is the opportunity cost of pursuing one option over another.

Don’t try to balance

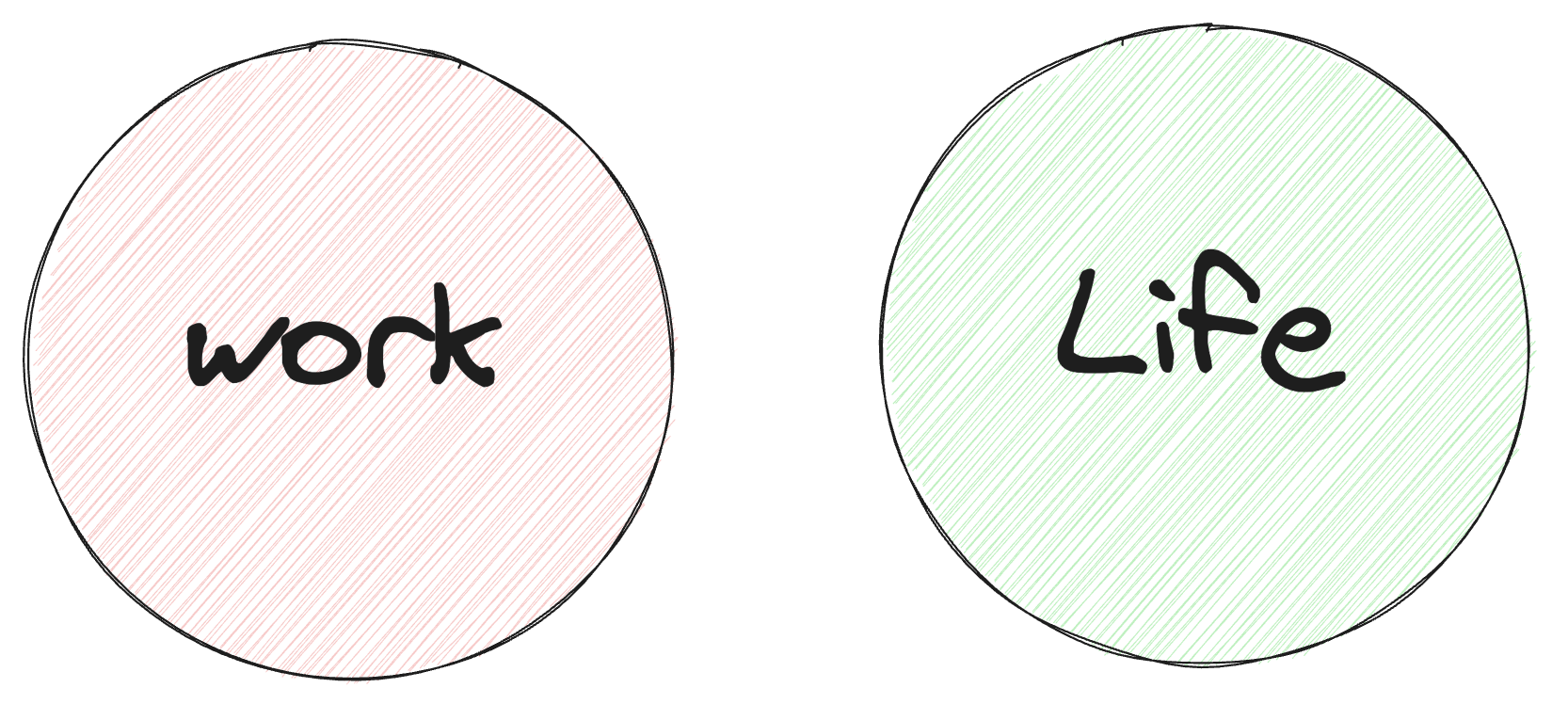

Many of us visualize work-life balance as these two non-intersecting sets of things that happen at work and outside of work to which we need to dedicate our time and energy.

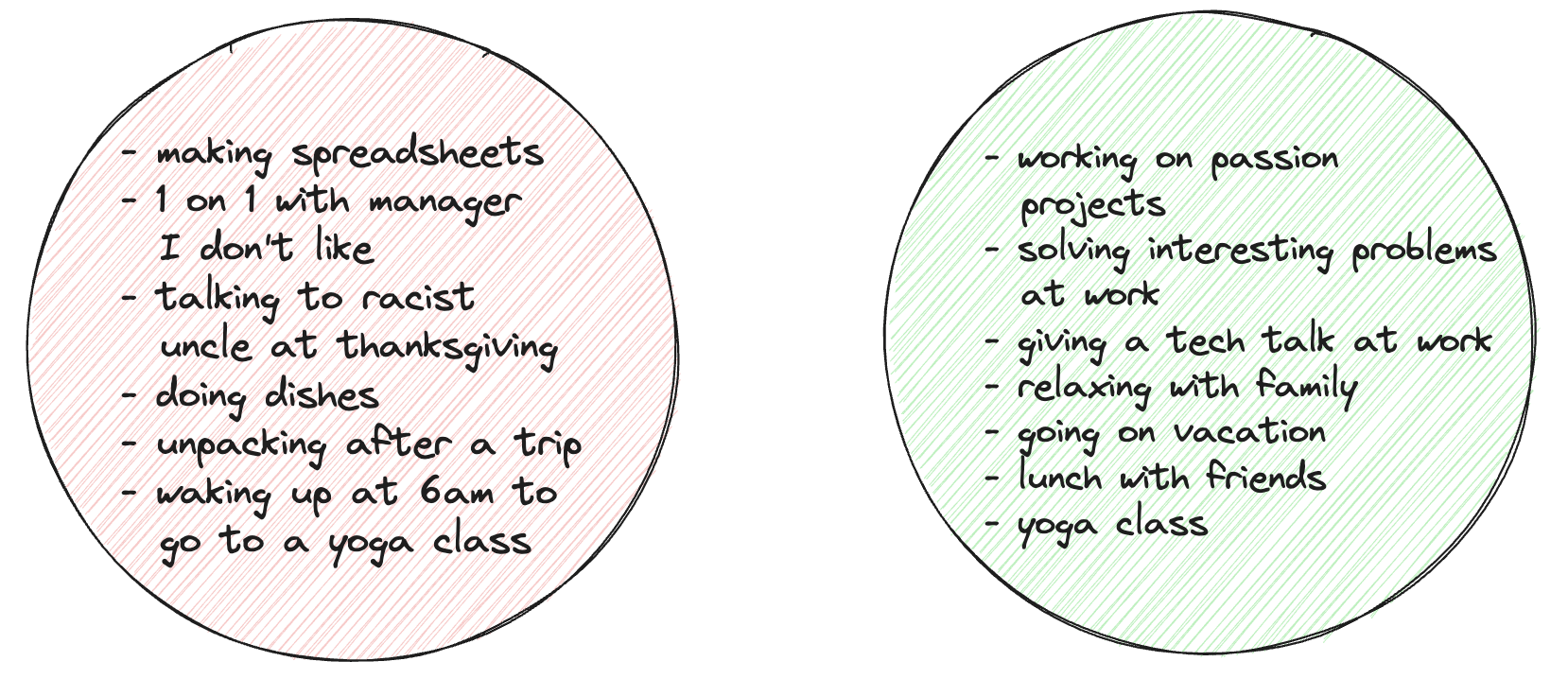

I like to split the things I do into these two buckets.

There’s this bias that a higher percentage of things we do at work drains us compared to things in our personal life. There are some truths behind this bias.

Interactions with people we don’t enjoy tend to be more common at work. In our personal lives, we have more control over who our friends are. We often have little to no control over who our managers and co-workers are.

Being able to spend our time doing what we enjoy tends to be more common outside of work. This is because people will pay other people money to do things that they don’t want to do, which are often things that are not enjoyable or easy to do.

We can see a pattern here: Things we do that energize us tend to be things we choose to do.

Many of us have passion projects like woodworking, rock climbing, and painting that we spend a lot of our own money to work on. They all require time and effort just like real work but we get negative monetary benefits from doing these things.

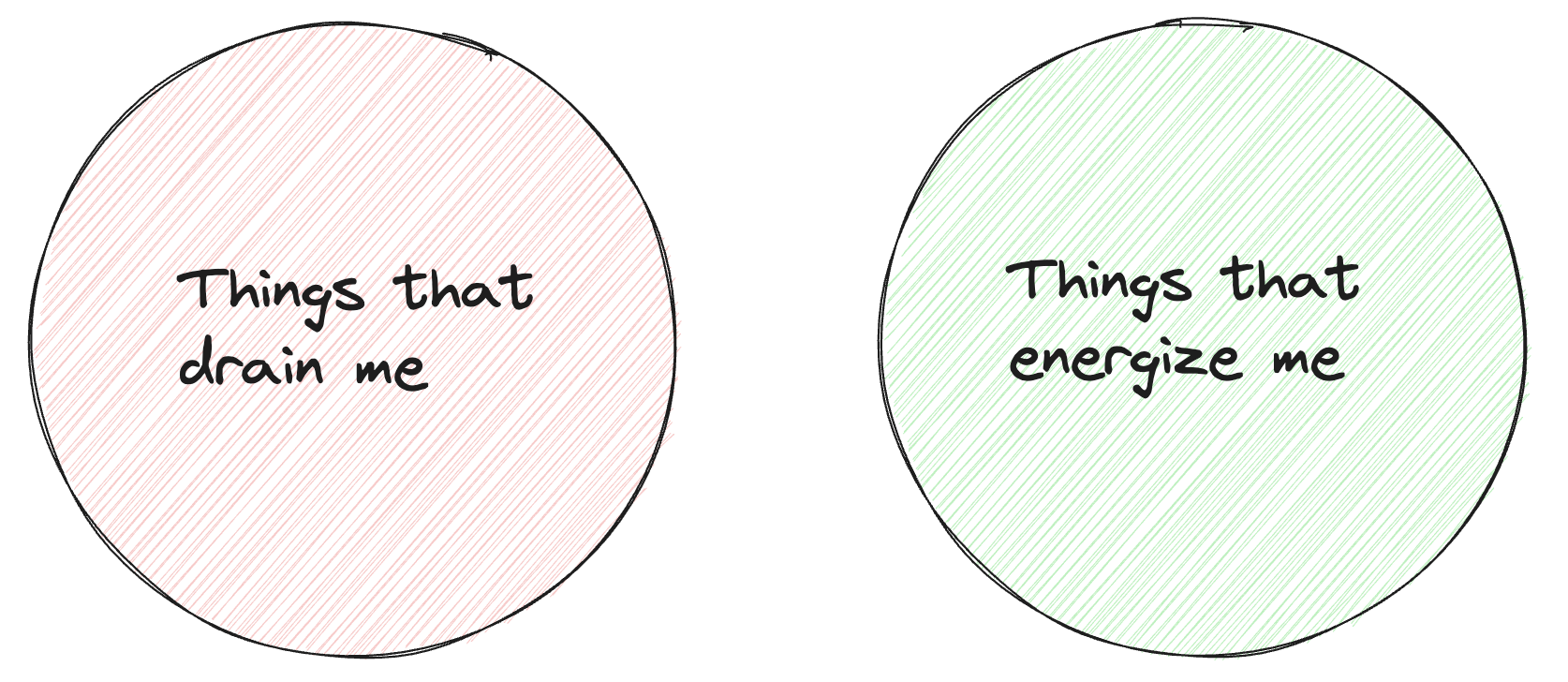

If we were to zoom into the specific things in these two buckets, we see that there are many things we do outside of work that are not enjoyable and drain us.

I hate doing dishes. If I had to choose between doing dishes and dealing with angry and annoying customers, I always choose the latter.

This is because I value learning and growth. I think interacting with annoying customers gives me the opportunity to acquire valuable skills in pacifying angry annoying people and discover ways to improve the product so the customers are not angry and annoying anymore.

There’s no benefit from doing dishes other than I get clean dishes at the end of it.

Many rewarding and enjoyable things you can do in life are unreachable without you first putting in hard work which is not enjoyable. For example, there’s an early morning yoga class I enjoy taking. To attend that yoga class, I have to wake up at 6 am and walk 50 minutes. The walk is not particularly pleasant, neither is waking up to that early morning alarm. But the yoga class is so good that it more than makes up for all the unpleasant things I have to do to get there.

Now, you may be tempted to ask:

Why do you have to walk 50 minutes? Can’t you take the subway? Is there an equally good yoga class that’s a 5-minute walk from you and is not so early?

These are the exact type of questions you should be asking yourself anytime you find yourself in a situation where you have to make a “sacrifice” in order to get what you want.

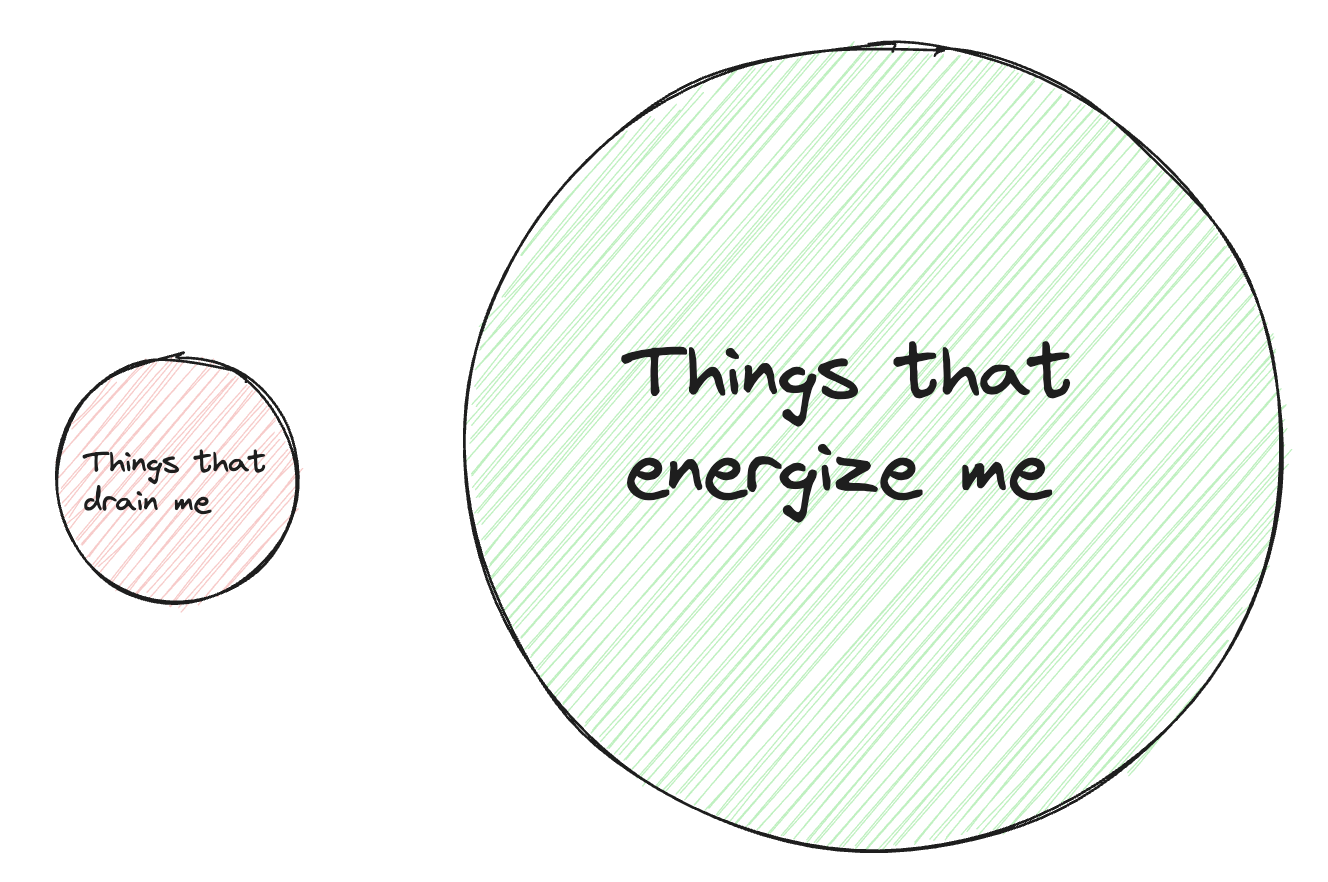

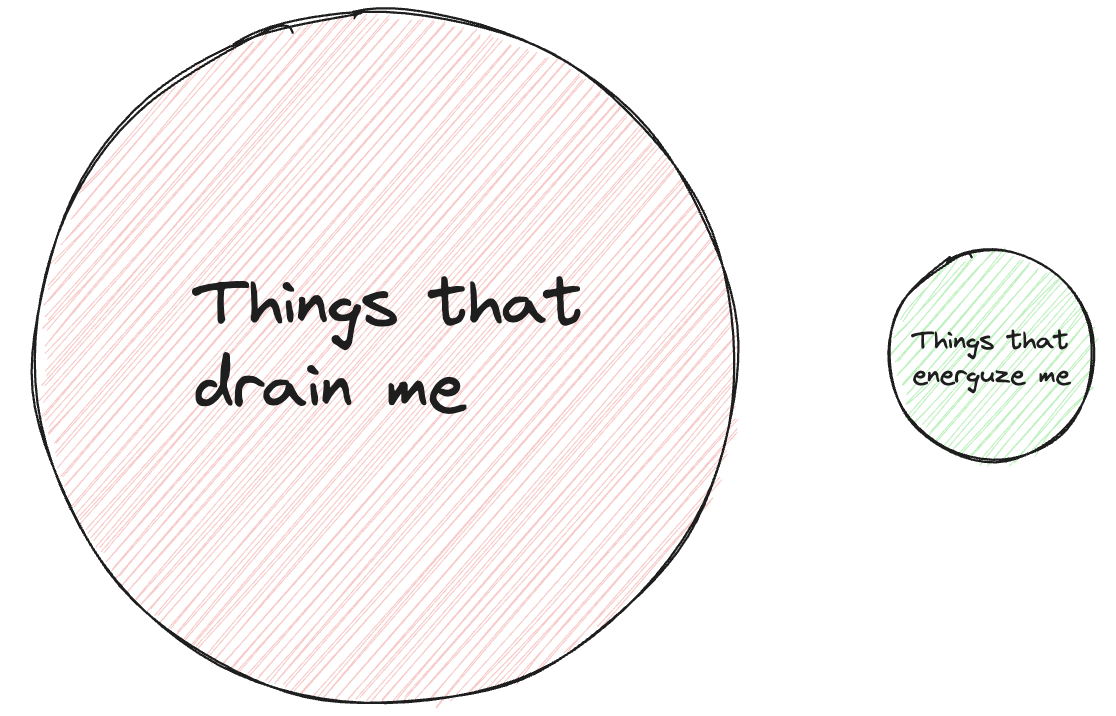

Don’t try to balance the “good” and the “bad”. We are never going to win with the balancing strategy because we have finite time, finite resources, and a finite attention span. The more time we spend doing things that drain us (make us unhappy), the less time we have to spend doing things that energize us (make us happy).

If you want to have more good things in life, you have to let go of the bad things in life to make space.

The important insight is these two circles add up to the same total area!

Here’s what a fulfilling life looks like:

Here’s what a miserable life looks like

All those mantras we hear in yoga classes make sense. These are some of my favorites:

- Let go of things that no longer serve us physically, mentally, and emotionally so we can make space in our lives.

- Hard things are hard until they become easy. There are always harder versions of hard things.

- If it hurts, don’t do it.

- There will always be things in your life you have no control over. Let them be. Focus on the things you do have control over.

Know when to delegate

During busy times when I need to conserve as much of my mental bandwidth as possible on important consequential decisions, I go with the default for things that don’t matter or let other people decide.

I like to go on autopilot for routine things like eating and working out to help mitigate decision fatigue.

For example, I take gym classes so I don’t have to make decisions on what to do at the gym and other people will count my reps for me. I also go to the same fast-casual takeout restaurant for lunch every day so I don’t have to spend any mental energy planning my meals.

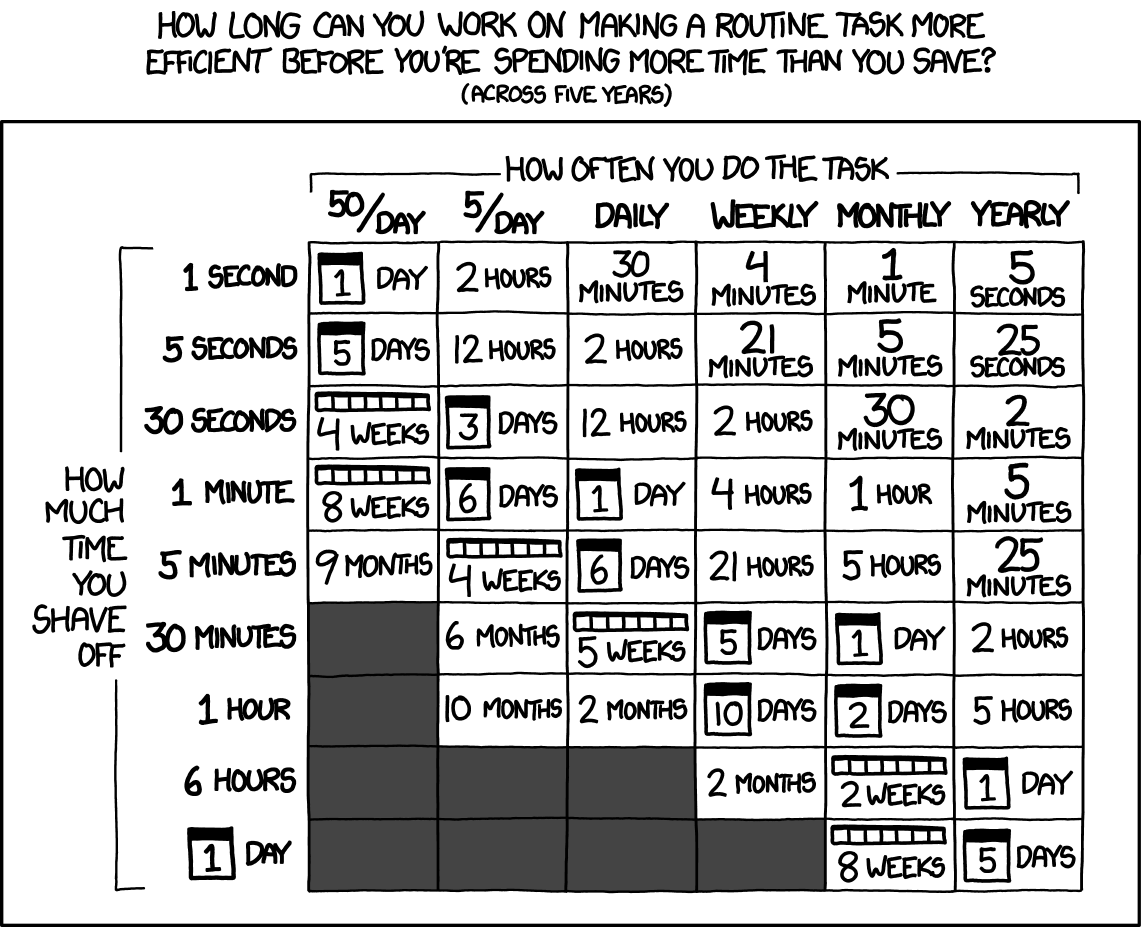

You can also delegate your work to software. We call this automation.

To determine if I should be looking at a tool to help me solve a problem, I start by asking this question:

Can an intern do this?

If you can describe a solution to have an intern implement, you can probably find a tool.

Delegating some of your work to other people or software comes at a cost, which comes in these forms:

- An up-front investment in time. You need to spend time finding the right trainer and the right classes to go to at the gym so you’d be happy doing that on a recurring basis. If you are looking to replace your routine work with a software solution, you need to spend time researching which software best fits your needs and you may have to spend time learning how to use this new tool and set up the automation workflow.

- A recurring cost in money. When you go with a delegated or automated solution, it will cost you more money. These come in the form of a subscription to a software product or gym membership. The per-item cost can also be higher (e.g. buying take-out lunch every day will cost more money per meal than making your own lunch).

There’s a tradeoff between time and money between doing it yourself vs automating and delegating. How do we decide what to outsource and what to do yourself? From a pure resource optimization perspective, there are three things I consider:

Consideration 1: How much do I care about the process?

Is it just something that just has to work and is there a special emphasis on how the work should be done? Is there a specific desired outcome?

Time spent doing something you are not good at is time that can be spent doing something you are good at.

If you are allocating time to do something you are not good at because you want to get better at it and it’s enjoyable for you, then maybe it’s worth your time.

But if you are doing it because it has to be done and you don’t particularly enjoy the experience of doing it yourself, you should consider delegation.

Consideration 2: What’s the opportunity cost if I do this myself?

Sometimes it may appear to be cheaper to do things yourself but doing things yourself can come at a steep cost - your time.

You can’t directly compare money and time but there’s a technique in cost-benefit analysis called monetization that converts all the pros and cons into monetary terms to enable calculation of a net benefit and comparison of different options in the same units.

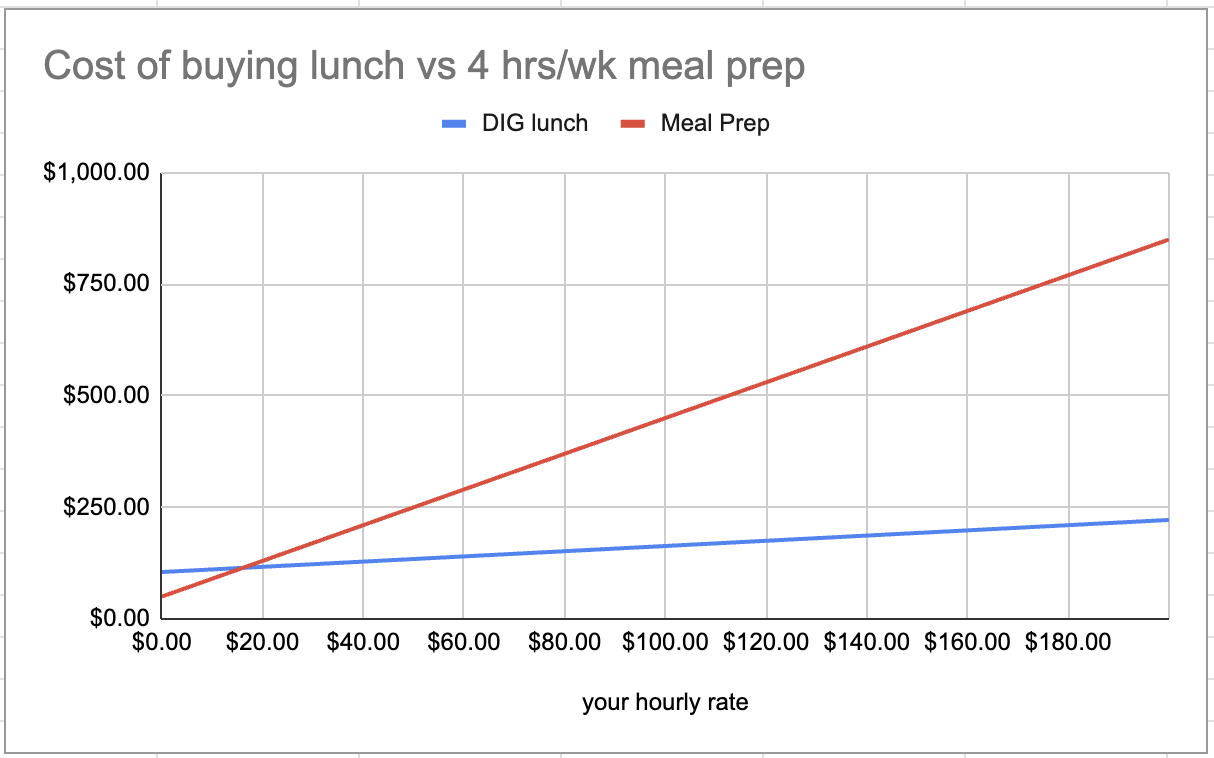

Let’s use this simple example of deciding whether to outsource lunch-making to other people (fast-casual restaurants).

Let’s assume that I don’t enjoy cooking, cleaning, and shopping. I don’t want to work on getting better at these skills and all I care about is being fed. I actually love cooking and I care strongly about what I put in my body but for the sake of performing this cost/benefit analysis, let’s assume I don’t have these other constraints.

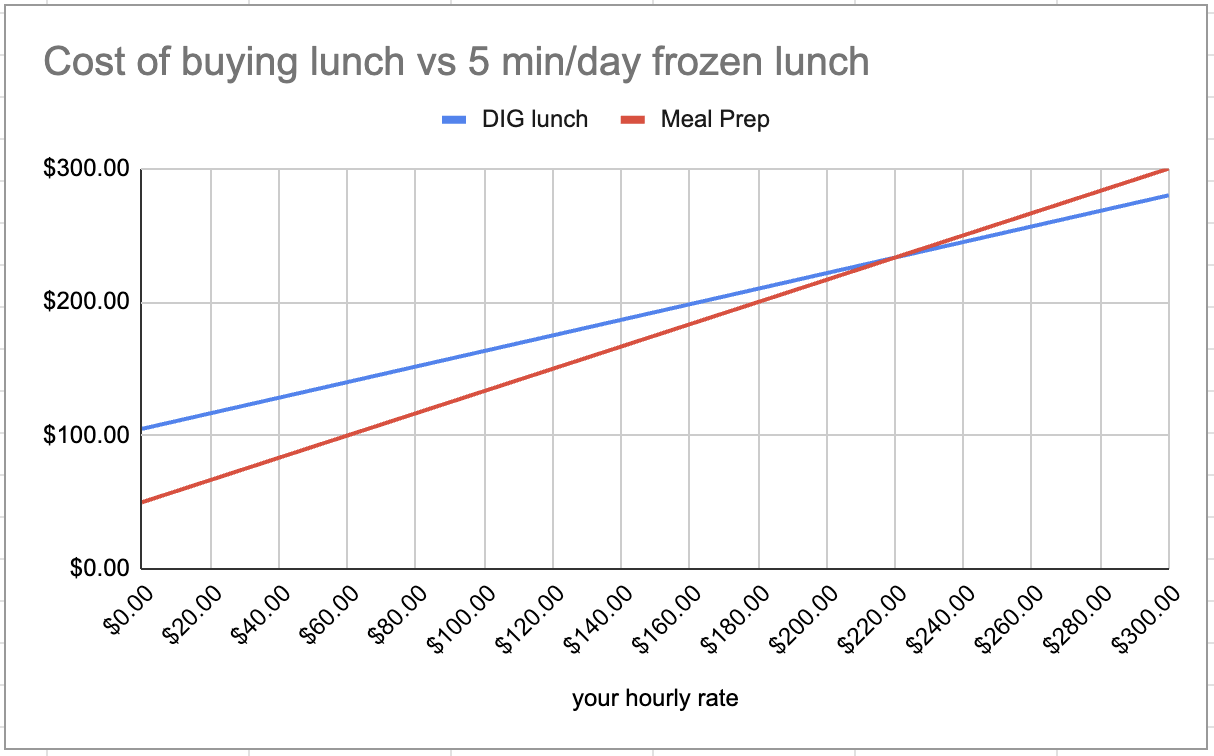

I can spend $15 for lunch 7 days a week ($105 a week). It’s more than double the cost of the alternative of cooking my own lunch which requires just $50 of ingredients from the supermarket.

But it only takes me 5 minutes to walk down the street, order my food, and walk back home. The alternative is I can cook my entire lunch for the week over the weekend, which requires 4 hours of shopping, cooking, and cleaning.

I’m a software engineer. Let’s say my time is worth $100/hr or ~$1.67/min. What’s the opportunity cost if I spend my time shopping, cooking, and cleaning instead of doing software engineering work?

| Outsource lunch prep | Cook my own lunch | |

|---|---|---|

| Material ($/week) | $105 | $50 |

| Acquisition (min/week) | 35 min | 240 min |

| Acquisition ($/week) | $58 | $400 |

| Total cost ($/week) | $163 | $450 |

Clearly, it’s way cheaper ($287/week cheaper) to outsource lunch-making for my situation.

We can generalize this by identifying a formula for computing at what point it’s less costly to cook your own lunch.

Assuming the following inputs to our cost/benefit analysis

- Meal prep takes 4 hours a week

- Lunch at DIG costs $15/meal and takes 5 minutes to walk there and back

It would only make sense to make my own lunch if I was making less than minimum wage.

What If I just eat microwavable meals for lunch 7 days a week? That would take 5 min/day to heat up lunch in the microwave (less than an hour per week).

The microwavable lunch cost would exceed the buy-takeout-lunch cost when your hourly rate exceeds $220. That translates to a $250,000 annual salary, which makes you the top 5% earner in this country.

It might seem strange that a top 5% earner would eat microwavable lunch to save money. In real life, decisions would not be made purely based on cost reduction argument but it’s a parameter for your optimization problem.

In real life, there are many other factors besides cost that you want to consider when making a decision, such as if that activity sparks joy even if there’s a high opportunity cost. These provide other parameters for your optimization.

Which parameters you care about in your optimization equation and the weight you assign to it depend on what you are trying to optimize in life.

To get the values of the parameters in your optimization, we relax the constraints by making some simplifying assumptions.

This technique is discussed in Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human Decisions for solving difficult optimization problems. It helps you establish a “lower bound on the reality”.

For this example, we made a lot of simplifying assumptions for this cost/benefit analysis problem like I don’t enjoy cooking, I just want to be fed regardless of what I’m consuming, and I spend the time I spend not cooking working and getting paid for that work.

But at the end of the day, most decisions we make are driven by what makes us happy, which is not always logical.

Mark Manson puts it best in Everything Is F*cked:

The Feeling Brain drives our Consciousness Car because, ultimately, we are moved to action only by emotion.

I’ll leave you with this anecdote.

My friend would spend an hour every Wednesday evening walking from a gym downtown to another gym uptown to go to a class. I asked him why he doesn’t just take the subway, which takes 10 minutes. His reply:

It’s free exercise!

Consideration 3: What’s the cost of migrating off of the delegated solution?

If you choose a software solution initially but your use case grows beyond that tool’s capability to support it, how much effort would it be to migrate to another tool?

If you hired someone and delegated the implementation of a mission-critical system to them. Then they decided it would be a good idea to build everything in a programming language that they invented. One day they suddenly get hit by a bus and there’s no one else in your company who knows that obscure language to be able to quickly take over that work (good luck with hiring people who know that language). How much money and time would it take to replace someone or the software they wrote?

Bus factor is the minimum number of people that would have to disappear to cause a critical system failure. A healthy organization should aim to have a large bus factor.

The desire to maintain a high bus factor and minimize migration cost contributes to a convergence of software tools and standardization across the industry. If your software is built using popular programming languages and libraries, then it would make it much easier to find a replacement for software engineers who left suddenly.

Prioritization and Efficiency

At an implementation level, becoming more efficient means making micro-adjustments to the way you move to save energy. This can mean introducing automation to replace the manual labor or sequence the things you have to do to reduce context switching.

But at a macro level, inefficiencies can be an inherent part of the system you are operating in and can only be eliminated if you make system-level changes or big lifestyle changes.

An example of the “status quo” that can slow you down is where you live. For instance, if you live a 1-hour commute from your work, then it’s like you are wasting 2 hours every day that you can spend working or sleeping. A lot of people with families who need to come to the city to work have pied-à-terre close to the office.

Mentally, there are many ways to “reduce the commute” from point A to point B which refers to reducing the cost of context switching from task A to task B.

For example, when I worked as the first engineer of Nova, I had to wear multiple hats and be a customer support lead and a product development lead.

In customer support mode, I need to be like a detective and do a lot of debugging and issue tracking to diagnose the root cause of the problem. In the product development mode, I need to be like an artist and do the deep heads-down work.

It’s very expensive to interrupt the deep work with random bug fixes. Inefficiencies are introduced every time I have to switch environments and my brain between being a detector and being an artist. That’s why I always dedicate an entire day or two every day to nothing but customer support and the rest is spent on new product development.

There are exceptions when you need to interrupt product development with customer support if it’s an emergency but the team needs to be clear on what is considered an emergency worth interrupting deep work for. It is not an emergency if a customer very angrily and loudly complains about a button that appears too close to another button causing them to accidentally click on the wrong button.

Have a system for Ruthless prioritization - I have a system for managing urgent and important tasks. I start my day by asking

What’s the definition of success for today?

This forces me to clarify the scope and break down the problem into small pieces that I can fit into one day. Each with a deliverable.

If the tool you use to prioritize is slowing you down, it’s not a good tool. For example, the complicated Notion database I had for prioritizing side projects required so much maintenance that it prevented me from having time to actually work on any side projects.

Pick the right movement pattern

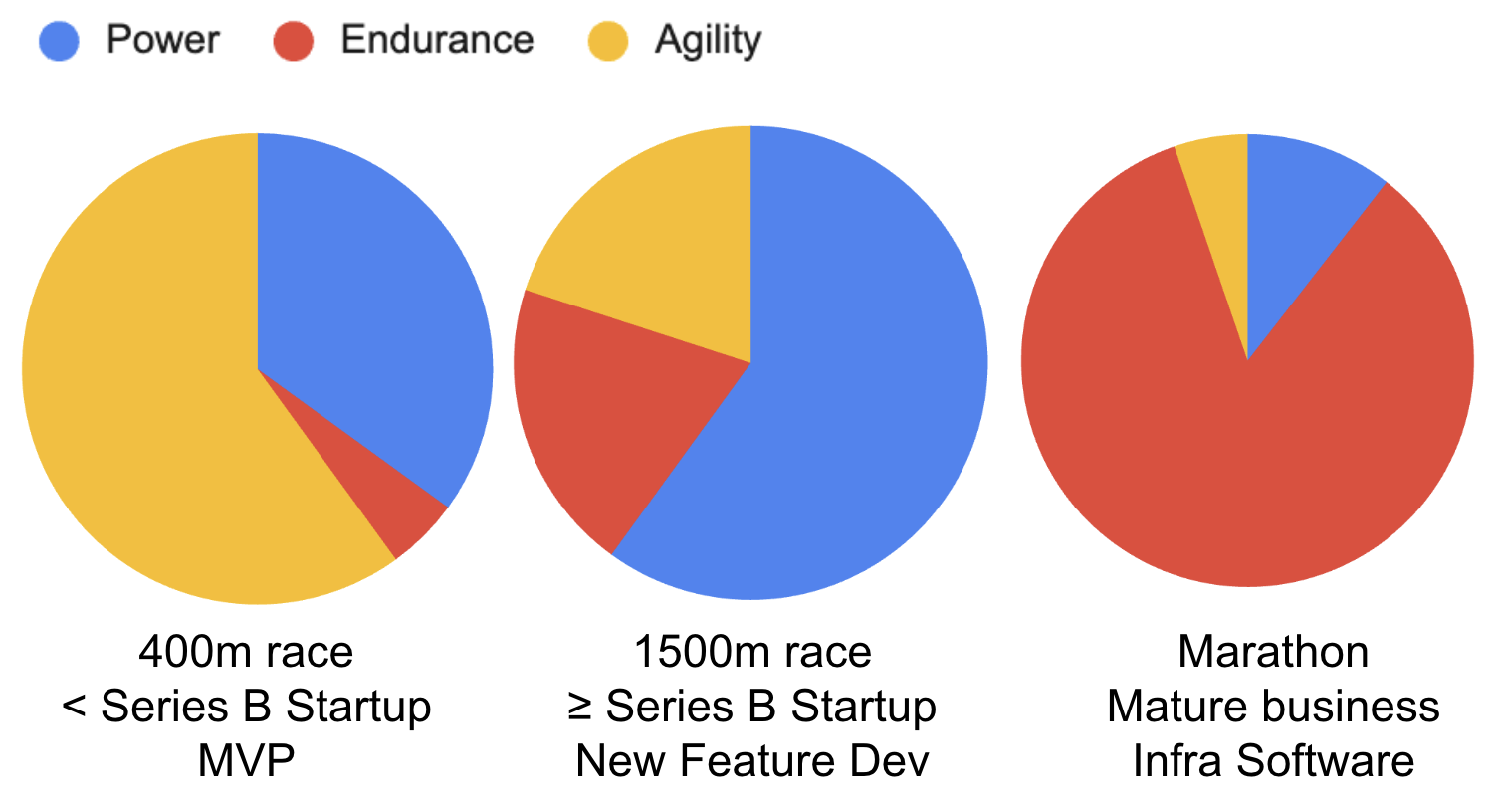

You need different movement patterns depending on the work you need to do.

For instance, if you are training to be successful at a race, how you run fast is a function of what type of run it is. Are you running a 100m sprint of a marathon? These different types of races require different movement patterns.

If you are rock climbing, are you doing a big wall multi-pitch climb or are you bouldering without a rope?

If you are building a business, is the business a small startup where you need to move fast and pivot fast or are you scaling a larger business with a lot of customers already?

If you are building software, are you writing code for a standalone MVP or an open-source library that will be used by millions of developers?

Generally, there are three areas to train for and how much you want to dial in on one of these training areas depends on what you want to accomplish.

- Agility - how fast you can change direction

- Power - how much distance you can cover in a short period of time

- Endurance - how long you can last

These usually have different names in different domains:

| Sports | Business | Software |

|---|---|---|

| Agility | Adaptability | Flexibility |

| Power | Scalability | Reusability |

| Endurance | Sustainability | Robustness |

In software development, KISS, DRY, and YAGNI are the analogs of the different movement patterns for software and product development.

Depending on what you want to accomplish, you may want to assign different emphases to each of these areas.

Chapter 3: How to operate at your upper limit

To be the most productive version of yourself, you need to be able to consistently operate at your upper limit.

Consistency is about sustainability and efficiency. We talked about conservation of energy, how not to burn out, and how to to make the best use of your time in the previous chapters. This chapter is dedicated to how to close the vision-ability gap to acquire a mastery of the requisite skills necessary for be at the top of your game.

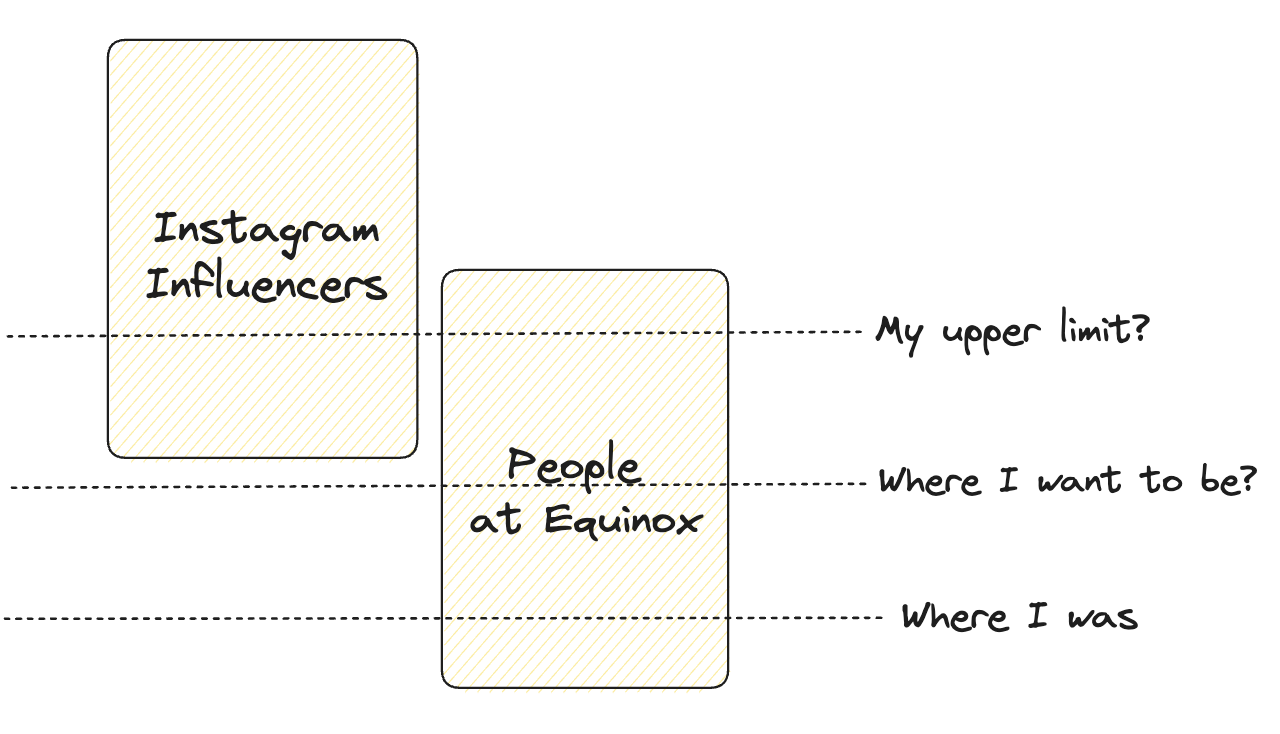

What can an upper limit look like?

If you are just starting out, you may not know what’s possible in general. After some time observing and learning from the people whom you consider role models, you might think that success means you should be like them.

But what is a success for other people may not be a success for you.

You may have an idea for what’s possible in general but you need to get a good sense of what’s possible for you before working on closing that vision-ability gap.

Another important thing to find out before you work on up-skilling is whether you want to operate at your upper limit at all and how long you can do it sustainability before you start burning out.

Another important thing to find out before you work on up-skilling is whether you want to operate at your upper limit at all and how long you can do it sustainability before you start burning out.

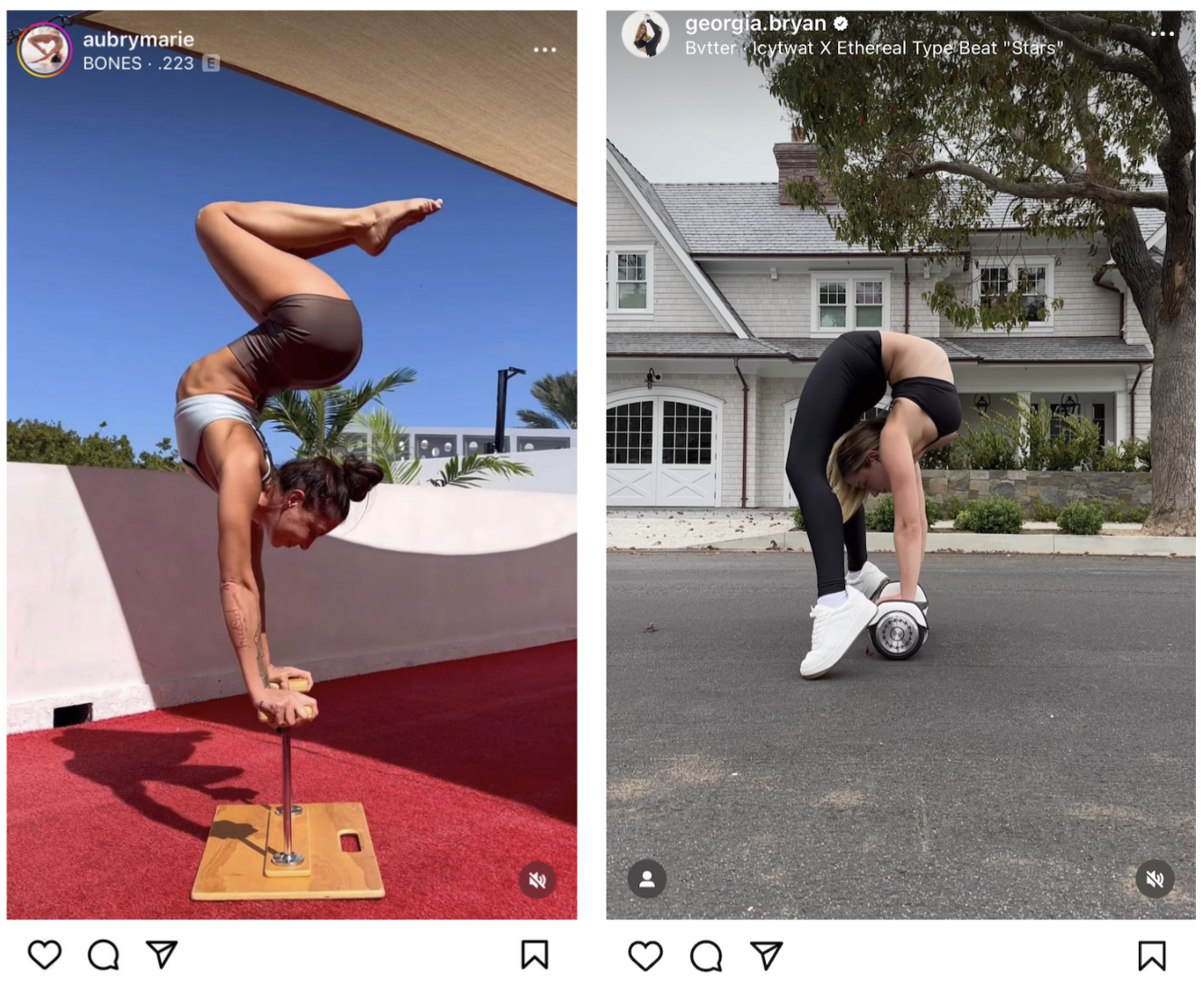

When I committed myself to getting good enough in yoga to be able to do fancy yoga poses like inversions and arm balances, I know I need to go to a lot of yoga classes. I followed some Instagram influencers who can casually lift into a handstand.

Instagram influencers gave me some data points about what’s possible for humans but many of these influencers had a background in gymnastics or had special bodies that allow their backs to bend in half. Those who are able to amass a huge following generally have some biological advantage or early mover advantages from their upbringing.

At Equinox, people in my yoga class come in different shapes and sizes. Some of them are Instagram influencers but many of them are regular people who started practicing yoga when they are in their 30s and through years of dedicated practice, acquired mastery of certain yoga poses.

Both Instagram influencers and my classmates in the yoga class gave me an idea of what I can achieve if I put in a ton of work to get stronger and more flexible. Although if I train really really hard for a long time, maybe it’s possible for me to be at the top of my yoga class and good enough to have lots of followers on Instagram, I may not want to do that because I rather spend my free time working on coding side projects instead of doing hand-stand practice 3 hours a day.

Now you have a good idea about what’s possible in general and some idea about where you want to be, it’s time to find out if it’s possible for you.

What is my limit?

Here’s the painful truth: You may never be able to close that vision-ability gap.

But that’s okay!

If you are working towards closing that delta, it’s progress and it’s worth doing.

Before working towards becoming a better version of yourself, you need to find out:

What am I closing the delta on? What am I working towards? What is the vision?

There are generally two types of limits that define the boundaries of your growth.

Limit 1: Physiological and Psychological

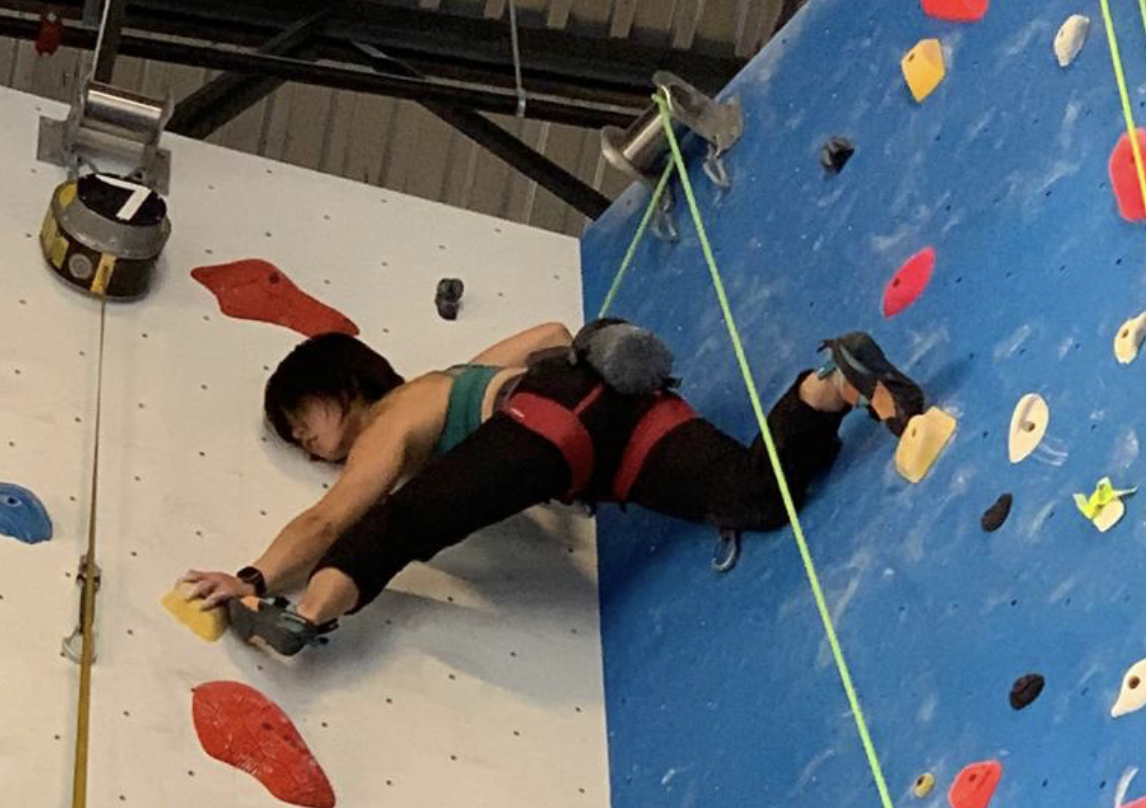

When I first got into rock climbing, I didn’t know what I was capable of as a rock climber.

Although in theory, I can be a great rock climber like Alex Honnold, I don’t want to free solo a 5.12d because I have a lower risk tolerance than he does.

Very early on, I tried easy roped climbing and bouldering. I noticed immediately that I’m terrified of climbing without a rope because I’m afraid of falling to the ground and injuring myself.

Since climbing without a rope is a psychological barrier for me to do more climbing and I need to not be afraid of climbing to do more of it to get better at climbing, I focused on becoming the best rope climber I can be.

Physical limitation is also a barrier. I’m very short so I can’t easily execute most people’s beta. Climbing gym routes are designed to be climbed by people who fall into the 5’8 - 5’11 range (I’m 5’1). But I use my shortness to my advantage - being short, I have better leverage I have very good balance and leverage on the wall.

I can do 5.12s if it’s a certain kind of climb that requires doing a bunch of pistol squats, laybacks, or crimps and traverses. I can’t do some 5.9 or 5.10s if it requires doing a lot of reachy pull-ups or dyno moves. I can do some moves like certain perches that are physically impossible for tall people to do without falling off the wall.

While there are some physiological advantages that you are born with (height or lack of), you can push that limit higher by training.

For rock climbing, you can train your finger strength using a campus board and lose unnecessary body weight to increase your strength-to-weight ratio. This requires more training outside the rock climbing gym and less eating.

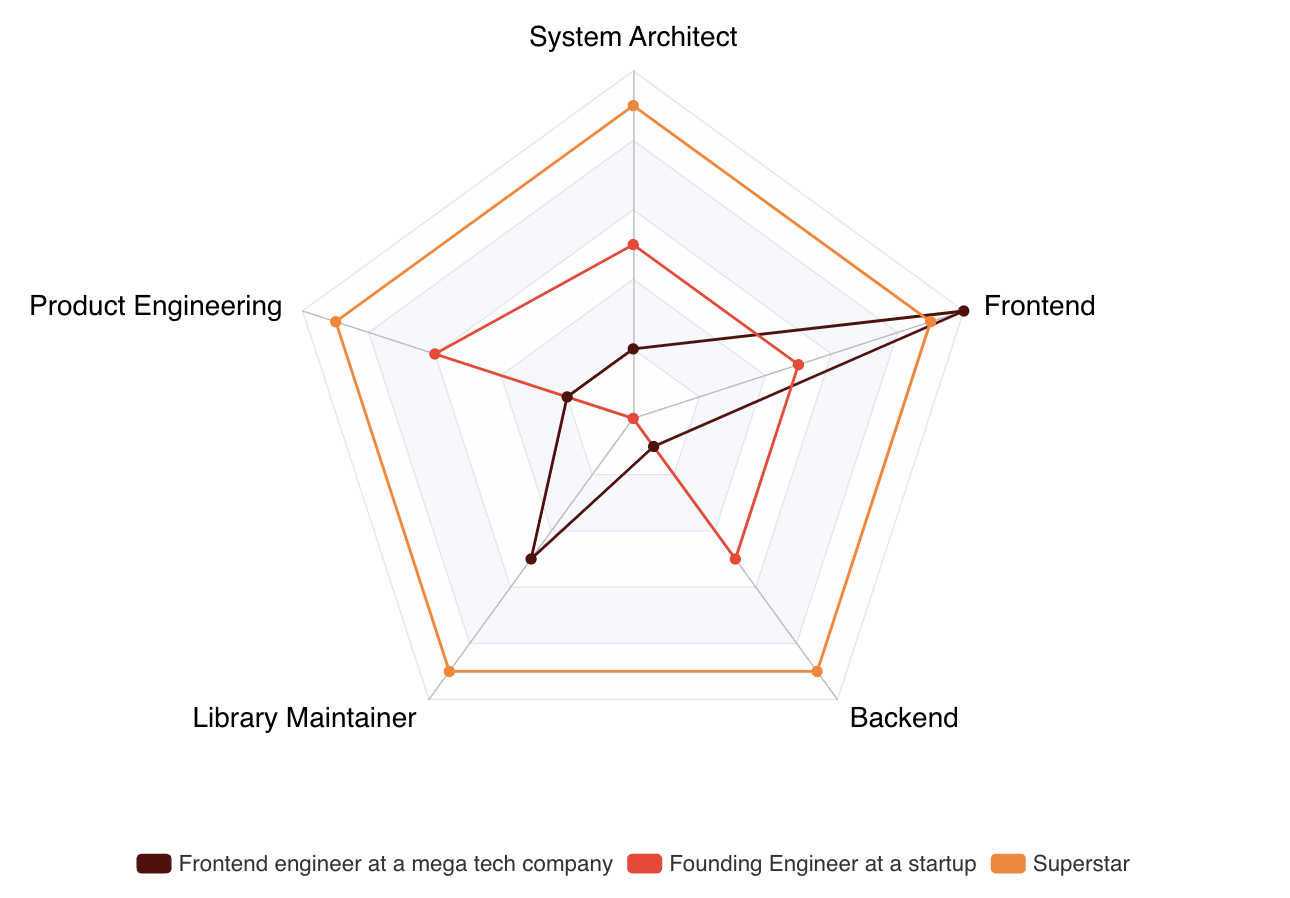

If you are working on advancing your career, you may also be interested in learning about what’s the best you can be in your profession. If you are a senior software engineer looking to level up, you probably don’t care to become an engineering manager if you don’t like dealing with people but that shouldn’t stop you from pushing your limits in the software engineering profession.

There’s plenty of room to grow in the IC track to become a lead software architect at a small company and a big company, which all come with different difficult but rewarding challenges. You can become a specialist in frontend or a generalist that can do everything across the stack. You may even want to explore entrepreneurship but that requires you to be able to work long hours without breaks and not everyone has the energy to do that.

I like to use this metaphor when I think about limits and growth:

Imagine yourself as a rubber band.

You can get stretched in many different directions but you can only get stretched so much until you snap or become permanently distorted.

I see permanent distortions in real life happen to people I know. One person works so hard that they get physically ill and can never seem to recover from their illness. Another person I know pushed themselves so hard into developing one skill that they lost their original passion which motivated them to develop that skill in the first place and became resentful.

Who doesn’t want to be a superstar? Superstars seem to be really good at everything they do. But superstars are like special kinds of rubber bands that seem to have a much higher elasticity than most other rubber bands. Not everyone can have a 160 IQ. Not everyone can have a back that bends in half and be double-jointed which let them casually lift into a handstand.

Don’t try to be a superstar and be okay with the fact that you are not a super stretchy rubber band and you can never be.

Rather, figure out the elasticity of your rubber band (an intrinsic property of you) and figure out a way to stretch it in the right direction as much as possible without breaking it or causing permanent deformation.

There are bio-hacks to increase your ability to get stretched without breaking, such as what I did to increase my power-to-weight ratio by losing a bunch of body fat and building a bunch of muscle. What I did for my body, you can do for your brain and your business too!

Limit 2: Resource

Resource is defined as anything you need to perform at the highest level. This includes money, time, energy, and attention span.

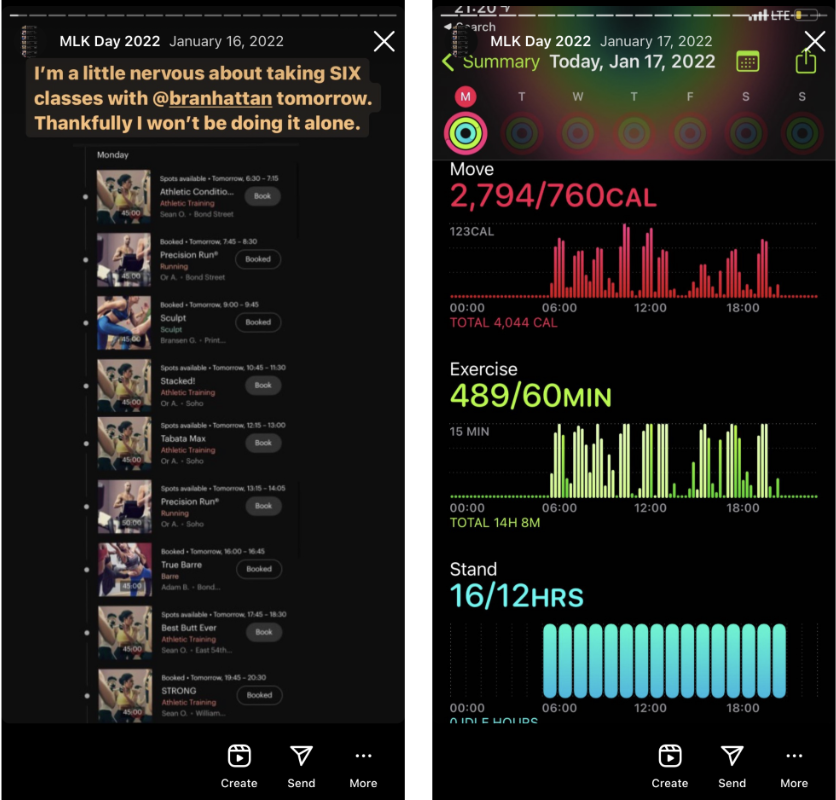

One day I wanted to find out my upper limit for athletic performance and endurance. So I took a day off work, got a good night’s rest, and took 9 classes at Equinox. My day started at 6:30 am and ended at 8:30 pm.

Because I had a day off from work, and as many classes as I’m able to take at any Equinox clubs in the city, I created this un-constrained environment that allowed me to experiment on determining what my limits are.

Am I going to take 9 classes every Monday because I can? No. But it’s good to know that I’m capable of doing that if I didn’t have any constraints.

Constraints like your work, family, and things you need to do to take care of your hygiene factors can prevent you from performing at your maximum potential.

Another way people determine what they are capable of in an unconstrained environment is through hackathons. During a hackathon, food, a place to sleep, and everything else you need are provided for you so you can dedicate 100 percent of yourself to problem-solving activities. Some companies like Pinterest, SendGrid, and Giphy were created during hackathons.

When I decide to work on a side project, I like to organize my own informal weekend hackathon with friends who also have side projects they want to work on. Then I tell everyone in my circle that I’ll be doing a hackathon that weekend so they know not to bother me.

For the side-project hackathon, we use the same format as a sponsored hackathon, including:

- A pitch event Friday night to introduce our projects

- Some scheduled check-ins during the implementation phase Friday night - Sunday afternoon, and

- A demo Sunday evening

These were some projects I completed during the weekend hackathons:

-

Slack Karma Bot which I added to my company’s Slack workspace and my teammates were using it to give kudos to each other.

Chapter 4: How to fail gracefully

Failure is not always a bad thing.

When we were babies learning how to walk, we failed all the time at walking properly. We’d take a few steps and fall but that’s part of the learning process. Learning and progressing in anything in life requires taking a leap of faith to stand up and take a step, then another step.

Falling is expected in the beginning because you don’t have the techniques and the muscles to be able to walk many steps without falling.

But even before you start learning how to take the first step, you have to have a plan for what you will do when you fall so you don’t fall on your face or twist your ankle.

Parents create a safe environment for babies to fall by putting them in a room with a rug to cushion their fall and buy them baby walking toys to reduce the chance of falling.

As adults, we do these much scarier things like rock climbing, changing careers, starting companies, and having children. You are going to be bad at these things in the beginning but without taking small steps and making incremental progress, how will you get better?

This chapter focuses on exploring the analogs of carpeted rooms and baby walkers for us adults to take steps on acquiring skills and accomplishing objectives in life without falling on our faces.

Deceleration Training

When you rely on momentum too much and you don’t have control, you are going to face plant. Deceleration training helps you learn how to fall gracefully.

In sports, a lot of injury comes from losing control when doing high intensity activities where you lift too heavy or try to change direction too quickly. There’s a lot of small muscles in your feet, around your ankles, hips, and shoulders which are used to stabilize your movements.

You need to train those small muscles to decelerate you when you need to change direction.

This is achieved through cross-training.

Yoga and barre provide excellent deceleration training because they focus on those little muscles that can help you achieve better balance and stability.

In software engineering, the “deceleration muscles” are like the logging and monitoring infrastructure and back-office tools that you invest in so when someone deploys a bug, it immediately gets flagged and there’s a way to quickly identify the root cause and roll back the breaking change before real damage happens.

In our personal lives, the “deceleration muscles” are the emergency fund we build up and the people in our support network who can provide a safety net to mitigate the negative consequences of getting laid off, marriage failure, and unexpected illness.

Risk Mitigation

Are you spending a lot of time working on risk mitigation or fixing the negative consequences of the risks you took which did not work out?

What if I told you that you don’t have to do any of this if you follow these principles:

- Don’t take risks you can’t handle

- Redundancy

- Defense in depth

I learned this blueprint for mitigating risks from my time working at Naval Reactors, where risk mitigation was a serious topic and you can cost the government billions of dollars, decades of work, and kill people if you get it wrong.

Don’t take risks you can’t handle

Decoding Greatness talks about how to “take the risk out of risk-taking” by shrinking the cost of failure.

In business, some companies like Costco create a completely different brand (Kirkland) just to try out some experimental stuff so if the new thing is a flop, it won’t ruin the company’s image.

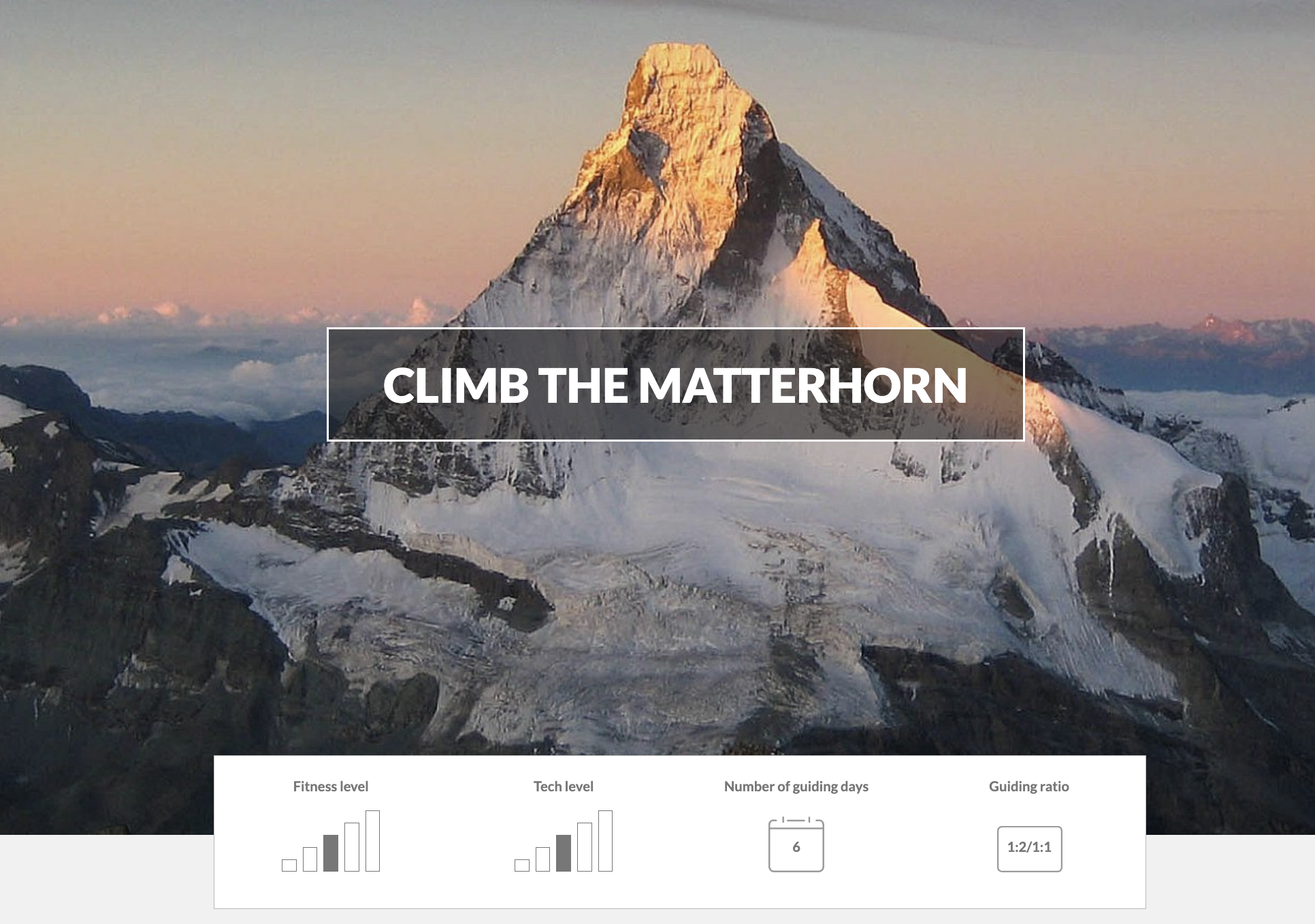

In rock climbing, the mountain guides excel at ridding the risk of a client killing themselves and other people by straight out refusing to lead people who do not meet the physical fitness and technical skill level required for this advanced level trip.

When I inquired about this trip with the company called Alpine Guides, I was advised to first take these mountaineering and climbing trips as training.

Redundancy

The guiding ratio for the Matterhorn is strictly 1:1. Why?

During the first ascent of the Matterhorn, 4 out of 7 people died because one person slipped and pulled three people down with him. The three survivors were able to cut their rope in time to ensure that they were not dragged down with the others.

That person who slipped was a single point of failure.

Nowadays when you hire a guide to climb the Matterhorn, you are working as a team of two. For the dangerous parts, you drape the rope behind a rock when the guide climbs up first so if you slip or they slip, you will serve as a counter-balance for each other. When you climb up, the rope is draped around another rock to serve as redundancy to catch you if you fall while the guide gives you a direct belay.

For the dangerous parts of life and in business, decouple the risky stuff you need to move fast on from the other stuff you can’t afford to lose. Make the experimental code/features as standalone as possible so if that fails, you can just cut it loose and it won’t drag the rest of your system/business down with it.

Defense in depth

For the Matterhorn, the entire mountain needs to be ascended and descended in less than 10 hours so you still have time to make it to the last Gondola taking you back down to Zermatt.

A lot of things can go wrong during these 10 hours. The Matterhorn has complicated route-finding, altitude, and risk of rock fall. Taking the wrong routes can lead you to dangerous loose grounds, in the worse case causing a rock fall which endangers the climbers below, and in the best case, causing a traffic jam.

Matterhorn guides practice defense in depth to ensure everyone climbing the Matterhorn gets to the summit and no one gets killed:

- Trips only run between July and early September when most of the snow melts, exposing dry rocks which are needed to move efficiently.

- Swiss guides and their clients go first because Swiss guides are the most knowledgeable about the routes and are less likely to cause rock falls or traffic jams.

- There are fixed ropes and pitons bolted to the mountain to assist climbers in tricky sections.

- Hörnli Hut right under the Mountain to ensure the ascent can begin at the crack of dawn.

- Solvay hut halfway up the mountain in case of emergency.

- Matterhorn guides are very experienced in big wall climbs that require excellent judgment when making tradeoffs between speed and safety.

In software, defense in depth is a common practice in cybersecurity to enable secure access (SSO, MFA, privilege controls).

It’s also implemented in code to mitigate certain unexpected errors that happen in production as described by Ryan Laughlin (Co-founder of Splitwise) in this tech talk.

Takeaways

To be the most bad-ass version of yourself, you have to be okay with being bad in the beginning and wisely invest your time, money, and energy to getting better.

If you are choosing to do hard things, it’s important to ask: What’s the net benefit? What’s going to happen when I fail? Can I get back up and continue on my path if I fall? Then, commit to the work needed to get better. Surround yourself with coaches and cheerleaders.

Know your limits and accept the reality that you are not a rubber band with infinite ability to stretch and snap back in shape. There’s a cost to getting stretched. There’s permanent damage that can be caused by getting stretched beyond your limits or going so far down the wrong path that you can’t get back to where you came from.

Be frugal with how you allocate your time. Don’t do negative work. Embrace the constructive form of laziness that encourages you to find more creative solution to your problems by challenging the status quo and to become more resourceful by seeking out automation.

Finally, respect the laws of physics that energy cannot be created out of thin air, only transferred and converted from one form to another form. Some energy will get lost during the transfer and conversion process due to entropy. Minimize the overall loss of energy from your system by using the techniques discussed in the mosts like reducing context switching and creating an efficient system to maximize the use of your energy towards things that create value.

This is how you get double the work done in half the time.