A few weeks after I turned 30, the world went into a lock-down. During the COVID-19 pandemic, I’ve done a lot of growing and learning as there is a lot of time to reflect on our values and think about better ways to live a more fulfilling life. There are two categories of lessons I’ve learned in my 30s. First is how to make better tradeoffs - opportunity cost, money vs time, efficiency vs effectiveness, and quality vs quantity. Second is how to prioritize.

1. Let the man win

When we are charged money for a product or service that was never provided or overcharged for poor service, it’s tempting to try to get our money back. When the decision to pursue a dispute is primarily principle-driven (motivated by the desire to correct some injustice), it could lead to a sub-optimal outcome.

There’s opportunity cost whenever we invest time and energy in a dispute. Depending on the type of dispute, there’s a varying probability of success that we can get our money back. No matter the outcome, we will lose the time, energy, and money that we could have invested in something else. Not to mention, there’s the non-tangible cost of mental stress and anxiety that we experience during the dispute.

Where’s the point of diminishing returns when you lose more than you gain by trying to argue for your money back?

When I was getting my driver’s permit, I passed the eye test without glasses (I don’t wear glasses). The DMV entered the information incorrectly into the system, which resulted in a wear-glasses restriction on my printed ID. I had to make an appointment to go to the DMV and pay $17 to get the information corrected. On one hand, it seems absurd that I’m getting charged for the mistake they made but in the grand scheme of things, I have more to lose than I can gain from trying to get my money back. $17 is like 4 cups of coffee. But starting a dispute could mean: I lose precious time trying to get the money back, filling out paperwork, going to the DMV again, and I won’t have the permit with the correct information mailed to me in time for my road test. I have more to lose than to gain from starting a dispute so I happily paid the $17 and moved on with my life.

But what if the money you are arguing for is substantial? What you consider to be a substantial amount of money depends on your financial situation.

I was involved in a dispute in which an airline canceled my return flight because they said I never showed up to board the outbound flight. There was obviously a mistake in their system that failed to record me boarding the outbound flight. It’s a common practice by airlines to automatically cancel the return flight for “no-shows” and keep all your money.

When I showed up to the airport to check in for my return flight, I was surprised to learn that I had no flight booked and the reason was that I was a “no-show”. In the interest of getting back in time, I bought a one-way ticket at the airport, which cost double of the original round-trip tickets. I filed a dispute with my credit card company for the original round-trip ticket for service that was not provided. I ended up losing the dispute. I could re-start the dispute and follow up in person by visiting the airline and the credit card company office to show the passport stamp from the outbound flight. But there’s no guarantee that it would lead to a different outcome. Having the boarding pass and the passport stamp doesn’t definitively prove that I boarded that exact outbound flight. I chose to save myself the headache and extra time trying to win this dispute. The money was substantial (over a thousand dollars), but it was not worth weeks or months of work and headache to get it back. I decided it would be better for me to let the man win.

2. Don’t be stingy on paid services you use all the time

I was on the Spotify free tier for a long time before I upgraded to Premium and I’m really glad I did. Having to listen to ads was a small annoyance when I only used Spotify to discover new music but when I really got into music during the pandemic, listening to ads all day contributed to a noticeable degradation in my day-to-day happiness.

Whether a subscription is worth paying for depends on the extent to which the subscription enhances your everyday experiences and happiness. How you assess the value of a subscription depends on your financial situation.

When I was a poor college student, I avoided paying for things like music, books, and hotels. I spent extra time finding free versions of everything I needed and opted to couch-surf or stay in hostels. In my 30s, I realized that the extra time and mental energy going with a cheaper alternative is not saving me that much money. Part of it is that my idea of what’s expensive has changed as I started to earn more money in my 30s.

When I travel, I happily pay for a hotel or Lyft to avoid spending hours commuting by public transit or coordinating with couch-surfing or Airbnb hosts. I pay for GitHub Copilot because it significantly improves my throughput. I spend over $300 a month on an Equinox membership because I like going to the best gym classes. Since I go to a lot of gym classes, the membership pays for itself.

3. Duplication is not always bad

In software development, the Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY) principle aims to reduce redundancy and improve efficiency by developing a framework for solving similar problems (e.g., abstractions and code sharing). But when we try to apply the DRY principle to every problem, we end up with overly complicated solutions on top of a rigid framework that is hard to evolve and maintain.

When we optimize our workflow to solve disjoint problems which are related by theme, we add more parameters to our problem solving and the solution becomes complicated and impractical to implement in real life.

A real-life example is when we try to optimize for logistics by trying to take out laundry and trash at the same time to avoid duplication of trips we have to make. Creating interdependence of trash and laundry could lead to undesirable effects like we would let trash sit around in our apartment because not enough laundry is accumulated to justify the trip.

Over-optimization can create artificial roadblocks to implementation. It’s important to recognize when we are optimizing for DRY just to minimize of duplication or there are actual non-negligible cost-savings.

In the trash and laundry example, there would be non-negligible cost-savings to do them both in one trip if we need to take out trash and laundry every day. But if the operations were not frequent enough or if the trash and laundry accumulate at different rates, maybe it is not worth dealing with no clean clothes to wear or sitting in a room with smelly trash just to save ourselves an extra 5 minutes going downstairs once a week.

For simple and infrequent problems, it’s usually better to tolerate some duplications to be more effective and quicker in solution development. But at scale, we have more to lose when we do not eliminate duplication.

In the context of software development, we can follow the AHA principle (Avoid Hasty Abstractions) to avoid premature optimization and find a balance between efficiency and simplicity.

We should only be implementing an abstraction and writing sharable code when we are confident that future use cases will not deviate from the current pattern. But deviation can still happen. Thus we need to ensure that evolvability, clarity, and maintainability are built-in features of the abstraction. This ensures that we can implement DRY without loss of clarity and maintainability.

4. Less is more

I prefer restaurants with a small menu because you can expect consistently high-quality food. When the menu is small, the kitchen can be more optimized for speed and quality because there is not a large inventory of ingredients to manage and a variety of recipes to execute.

The same principle applies in life. Just like a kitchen, you are limited by resources and time. When you have fewer things to work on, you can optimize your workflow to be more effective at the few things that really matter. This requires prioritization based on your values and goals.

For example, when you have a large number of friends and acquaintances, you have to manage a large number of relationships. It is difficult to have deep meaningful relationships with all of them. You have to prioritize your time and energy to maintain the relationships that are most important to you.

Another example is when you are trying to do too many things on your trip. You are visiting a different European city every other day. The logistic of packing and unpacking your luggage, finding a place to stay, and getting around the city is a hassle. You don’t have time to enjoy the city because you are always on the go.

Generally speaking, “less is more” is a tradeoff between quantity and quality. While having variety and options can make things more interesting and make you feel less restricted, juggling too many things at once can cause inefficiencies from context switching and loss of focus.

5. A stack is the most effective way to maintain a side project to-do list

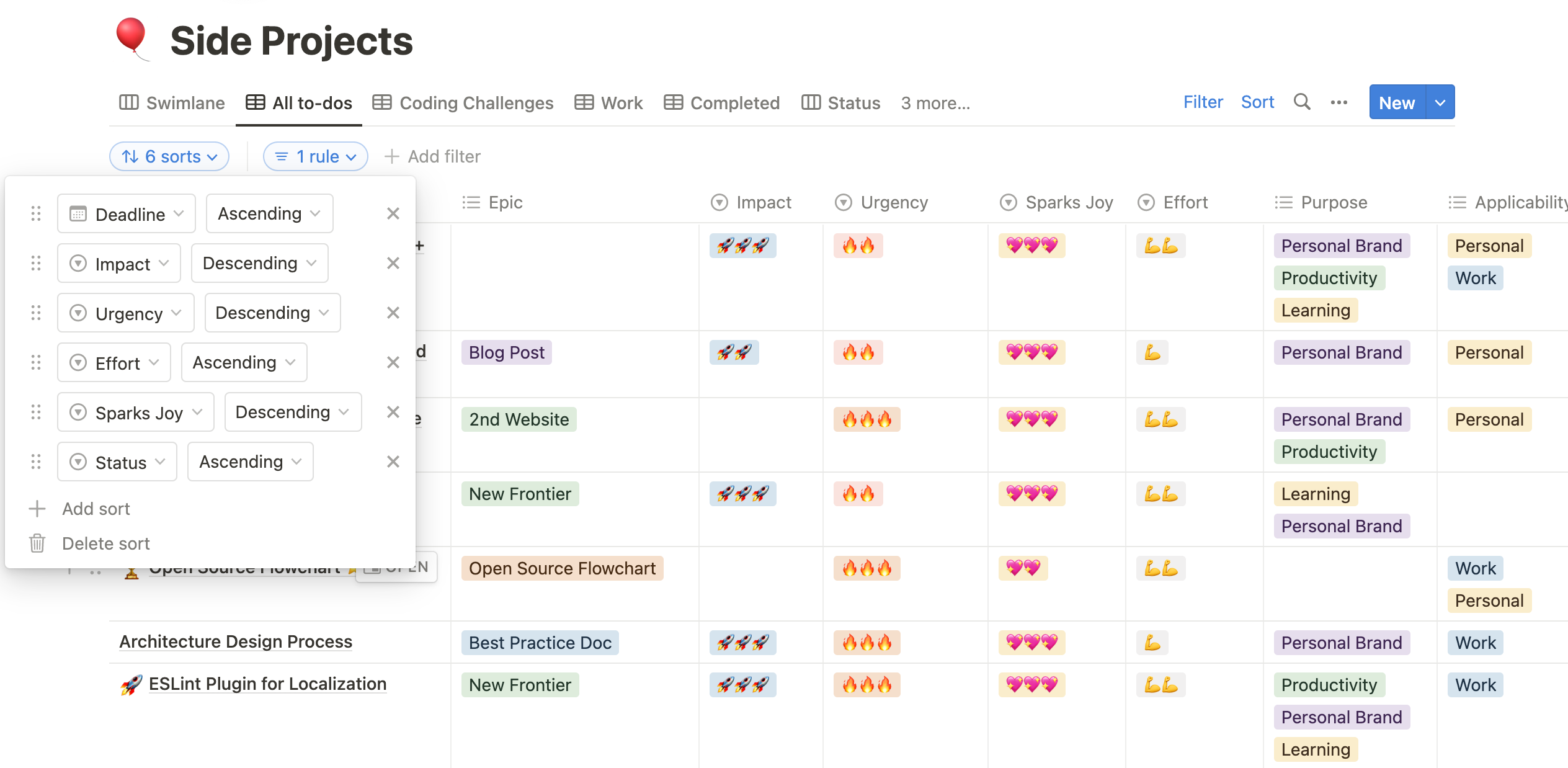

I used to have a complicated system for organizing my growing list of side project to-dos. I created a system in a Notion workspace to track and sort a backlog of side projects to-dos based on a score I assign for its urgency, importance relative to some life area that I was trying to optimize for (e.g., career development), how much stress or FOMO it would cause me if it didn’t get done, and how much enjoyment I would get if I worked on it.

The idea is that this sorted list would tell me what I should be working on in my free time so I don’t get distracted trying to work on too many different things.

Using a priority queue is a fine way of organizing your todo-list if the parameters for your prioritization don’t change that much or if your list is for routine things like laundry and taxes or things with hard deadlines like packing for a trip.

However, the tasks I was keeping in my todo-list are related to hobbies and self-improvements. These tasks are important but not urgent and their importance is a function of how I felt at the time when I added the task to my project backlog.

As my todo-list grew and my interests shifted, the list became frequently out-of-date. I found myself spending a lot of time going through items in the list to update the fields for prioritization to the list to reflect what mattered to me at the time. I was a slave to the list and the list was not serving me.

The weakness of this system is that it tries to quantify your overall feeling about something that is unquantifiable. The score is a function of your mood and how you feel at the time. At different points in time, you may give different scores for the same task.

Feelings and situations can change very quickly and unexpectedly. Our values and beliefs can change too. A hard-coded prioritization system can become irrelevant and restrictive.

So what’s the best system to keep a project todo-list that is always up-to-date and relevant?

The answer is to use a stack. A stack is a data structure that follows the LIFO (Last In First Out) principle. You can think of a stack as a stack of papers on your desk. The last paper you put on the stack is the first paper you take off the stack.

The stack is very responsive to changes in your life and your belief on what’s important and urgent at the time. When you get inspired to work on a new project, you add it to the top of the stack so it has a higher chance of it being done. For creative tasks, you can’t schedule a time to do it in the future when you are inspired now. It’s better to get to it right away while the inspiration is still there.

If you are suddenly inspired to work on something that was added earlier in the stack, that gets bubbled up to the top of the stack (or you can re-add it to the top of the stack as since stacks allow duplicates).

Mentally we have pre-sorted everything we add to the stack so the stack is really a reflection of how our brain is thinking about the priorities of the things we want to work on.

As old projects get pushed down by new projects in this stack, you may never get to work on the old projects. But that’s okay. The point of the stack is not to help you get things done. The point is to help relieve the stress of having too many things to do and to help you focus on the things that are most important to you at the time.

If you need a system to help you actually get things done, I suggest using the priority queue and assigning a deadline.

I actually use both a stack and a priority queue for maintaining all my to-dos. For example, if I get inspired to write a blog post, I add a task to my stack to just brain dump into a draft blog post. Then I create a task in my priority queue to edit and publish the blog post with a deadline.

6. Work-life balance is a false dichotomy

Work-life balance is a framework commonly used to prioritize how we spend our time. An important assumption that underlies this framework is that work and life are two separate things and the demands of one’s career and the demands of one’s personal life are mutually exclusive. In reality, it’s more like a Venn diagram.

Another problem with the work-life balance framework is that it compartmentalizes the things you do with your life into a bucket for work and a bucket for life and you are supposed to achieve a balance between these buckets.

Regardless of the context, you are spending your time doing things that either energize you or drain you.

There are things we have to do for both life and work which drain us and we can’t avoid doing. In life, I have to do laundry and dishes which drains me. I wouldn’t want to stop doing enjoyable things for work because it’s time to do laundry and dishes.

Instead of working on achieving a balance between things you do for work and things you do for life, a better problem to solve is to figure out how to maximize our time doing things that energize us and minimize or eliminate the need to do things that drain us.

At work, our companies invest in tools and processes that automate the repetitive and mundane tasks because there is a strong correlation between productivity and profit. Happiness can be a result of productivity.

In life, we can do the same. For example, I eat out a lot so I don’t have to do dishes. What energizes and what drains depends on the person and the situation. Sometimes if I have a stressful day, I find it therapeutic to do dishes to get this “small win”.